Colossal Youth and Horse Money, Pedro Costa

Where Are Now the Dreams of Youth ?

“I have a dream.” Martin Luther King, 1963

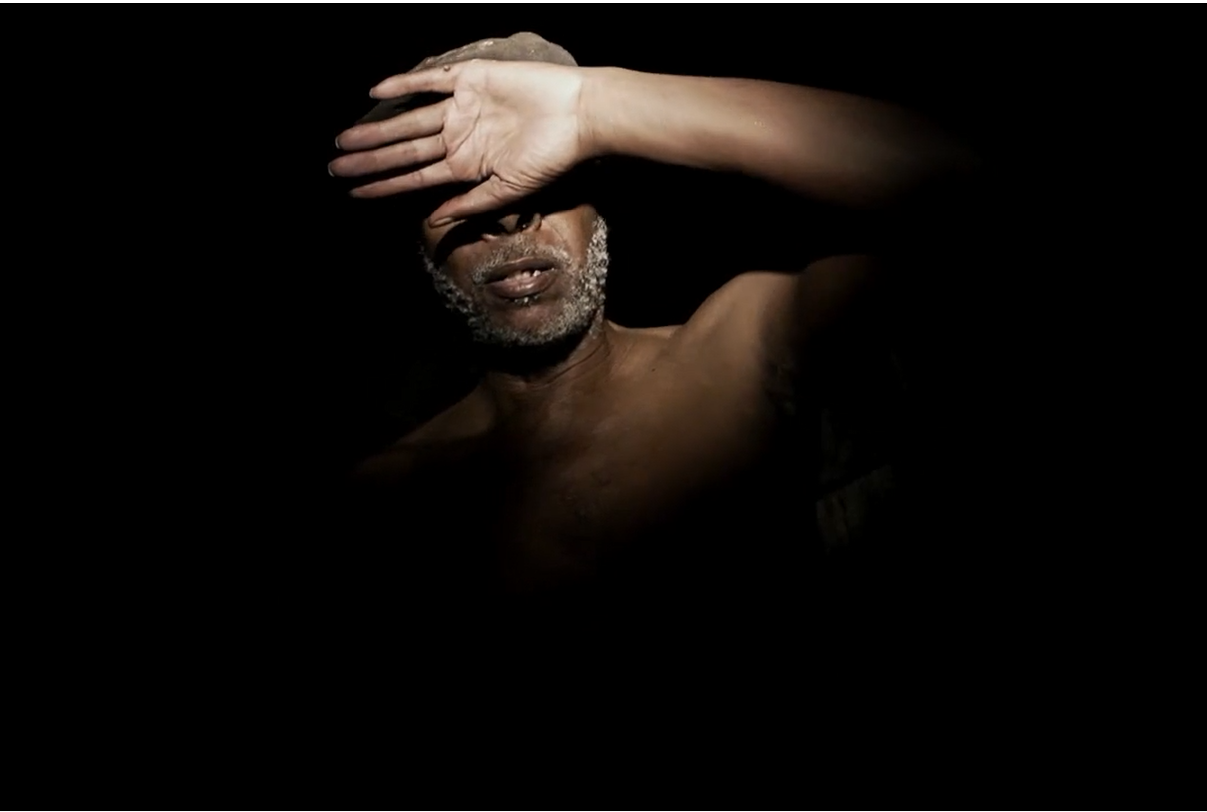

“I had a nightmare.” Ventura, 2014

According to Pedro Costa, Colossal Youth (2006) is a remake of John Ford’s western-cum-procedural-drama Sergeant Rutledge (1960): in both movies, a black man with an imposing physique is called to stand tall and stand up for his millions of brothers and sisters humiliated by centuries of enslavement and racial segregation. In the former film, the colossus is Ventura, a fifty-something Cape Verdean who emigrated to Lisbon in his teenage years, in search for a job and a better future away from Portugal’s “overseas province” Capo Verde; in the latter, 45-year-old Woody Strode plays the eponymous hero, a former slave who enlisted in the 9th US Cavalry in search for dignity and integration.

Both Costa and Ford seem to have succeeded in condensing the hopes, sorrows and sufferings of a whole people into the words and gesture of one single screen persona. For example, the Portuguese filmmaker stated that, after watching Colossal Youth, a young man from Fontainhas, the now-demolished Lisbon slum where Ventura and many other impoverished immigrants used to live from the late 1960s until the late 1990s, said: “Ventura, you’re a piece of shit every day in this neighborhood and we see you up there [on the screen] and you’re all of us !”[11][11] Mark Peranson, L’avventura : Pedro Costa on Horse Money. See also Cyril Neyrat, Dans la chambre de Vanda. Conversation avec Pedro Costa, Nantes: Capricci, 2008, p. 161: “Comment as-tu fait ça, Ventura? Je t’ai vu toute ma vie, ici, comme un con, et là on était au cinéma et tu étais fort, tu étais très beau!”. The very same concept was expressed by Strode himself with regard to Sergeant Rutledge : “[The movie] had dignity. John Ford put classic words in my mouth. […] You never seen a Negro come off a mountain like John Wayne before. I had the greatest Glory Halleluja ride across the Pecos River that any blackman ever had on the screen. And I did it myself. I carried the whole black race across that river.”[22][22] Woody Strode interview, quoted in Tag Gallagher, John Ford. The Man and His Films, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986, p. 375. After Sergeant Rutledge, Strode would play a few more heroic roles, for example gladiator Draba in Stanley Kubrick’s Spartacus (1960) and Maurice Lalubi in Valerio Zurlini’s Black Jesus (1968). Nevertheless, I would like to propose that the affinities between the two films and their respective colossuses end here.

Sergeant Braxton Rutledge is a man who first loses his rank in the 9th US Cavalry and then regains its position of responsibility by heroically defending his stranded former regiment during an Apache ambush. “Majestic” and “epic” are the only adjectives appropriate to describe the scene in which Rutledge is given back command of his platoon after dispersing the Indian threat. Strode steps on a little mound of earth and strikes a monumental pose against the clear night sky – he stands chin-up, holding a rifle that looks like a toy gun in his mighty right hand. He is framed from his knees upwards, from a slightly low angle: bending the laws of physics for the sake of mythopoeia, he appears to tower over the full moon in the sky. The close-up that follows maintains the slightly low angle both to magnify Rutledge’s grandeur and to allow the moonlight to sculpt his cheekbones and jaw as he slowly turns his head to survey the horizon. All this while Rutledge’s men cheer him by singing the song Captain Buffalo : “Said the Private to the Sergeant: ‘Tell me, Sergeant, if you can… / Did you ever see a mountain come a-walking like a man?’ / Said the Sergeant to the Private: ‘You’re a rookie, ain’t you, boy? Or else you’d be a-recognizing Captain Buffalo’.” Crucially, the shots in which we can admire Strode’s posing are point-of-view shots of a wounded black soldier in his sleeping bag, and of the sympathetic white leads lying in a trench : everybody looks up to the title-character in this scene.

Overwhelmed by Ford’s powerful audiovisual rhetoric, we are absolutely sure that one day all people in America will be treated equally, regardless of the color of their skin. Still, neither Ford nor anybody else involved in Sergeant Rutledge seem to know when this will happen. Indeed, “someday” is Rutledge’s favorite adverb, judging from lines such as “We been hunted a long time too much to worry. Yes, it was all right for Mister Lincoln to say that we were free, but that ain’t so, not yet. Maybe some day, but not yet,” and, to a dying black soldier who was fatally wounded on duty, “Someday your family will be awfully proud of you.” But no matter how the word “someday” refers to an indefinite future, there really is no room for defeatism in Ford’s film, only great hopes for a better tomorrow: Strode is the black John Wayne – he may have his moments of fear and doubt, but he is a leader. He may die before the dream of black emancipation is fulfilled, but he set the example for his brothers and sisters. He opened the track for his people to follow in line, the parade being a favorite Fordian metaphor for the continuation/preservation of a collective ideal/dream/mission beyond the mortal life of the individual.[33][33] Cfr. Gallagher’s acute analysis of the parade metaphor throughout the “1948-1961: The Age of Myth” chapter of John Ford. The Man and His Films.

On the contrary, in Costa’s Sergeant Rutledge “remake,” Ventura – though having the appearance of a giant – is far from possessing the strength of Strode’s Rutledge. We can easily imagine that in his youth the Cape Verdean used to be as strong as a bull, “built like Lookout Mountain, taller than a redwood tree,” as the lyrics to Captain Buffalo say[44][44] The full verse of the song goes: “Have you heard about a soldier in the US Cavalry / Who is built like Lookout Mountain, taller than a redwood tree? / With his iron fist he’ll drop an ox with just one mighty blow / John Henry was a weakling next to Captain Buffalo.”. Ventura was so strong, in fact, that he built his house in Fontainhas with his own hands in the 1970s, while doing all kinds of underpaid heavy jobs to support his family back in Capo Verde, with the hope to reunite it one day in Lisbon, the land of opportunity. But all this – the youth, its energy and dreams – is gone in 2006: what remains is an old, sick man, “a diabetic, an ex-alcoholic, a diagnosed schizophrenic and anemic – that’s the picture.” declared Costa “His daily life is the same as that of every unemployed, retired, handicapped underdog in the world. It’s the life spent in the corner of the bar, with bleak horizons and nothing beyond a deck of cards and two or three glasses of wine”.[55][55] Aaron Cutler, Horse Money : An interview with Pedro Costa. As a matter of fact, Colossal Youth‘s original title “Juventude Em Marcha” [Youth on the March] sounds an additional note of bitter irony, if the film is compared to its source of inspiration Sergeant Rutledge : the 2006 Ventura is neither in his prime nor leading his people towards a better tomorrow. Actually, the only parade in Colossal Youth is an off-screen funeral procession taking the corpse of young heroin-addict Zita Duarte to the cemetery…

Since Ventura cannot look towards and forward to the future, he cannot help being haunted by a past marked by the irremediable loss of everything that matters in life. From the very first scene, featuring the knife-wielding ghost of Ventura’s wife, Colossal Youth is a long, painfully detailed inventory of what the immigrant has lost during his stay in Lisbon: romantic love, relatives and friends, work, health, native land, home… Yet, even if the past is a pile of shattered dreams and broken memories, and there really is no future other than death, Ventura’s present is not at all meaningless. Ventura, too, has a mission and does his share of marching in order to fulfill it, just like Captain Buffalo who “will march all night and [will] march all day / And he’ll wear out a twenty mule team along the way.” In fact, in spite of his constantly spinning head and his aching body, Ventura patrols the streets of suburban Lisbon searching for his equally puzzled, sick and lost “sons” and “daughters,” who are in turn looking for him to make sure that he eats proper meals and takes his pills regularly. Basically, Colossal Youth is a film about an old man keeping “the family” (read: the destitute Fontainhas community) together, as the powers that be try to destroy it by bulldozing people’s “clandestine homes” (as seen in In Vanda’s Room, 2000), by scattering the now homeless across newly-built, poorly-made “neighborhoods for the poor” (Colossal Youth), and by resorting to legalese threats, police brutality, forced repatriation (Tarrafal, 2007; Rabbit Hunters, 2007; Our Man, 2010). But keeping family ties alive in Lisbon in the 2000s might be far too hard a task for old Ventura alone. It is enough work to drive a sane man mad…

Flash-forward 8 years, Horse Money (2014) shows us Ventura in a doctor’s office. His hands are shaking quite a lot, and he seems to be in very bad shape: troubled, frightened and sleepless. To the off-screen doctor – or is it a policeman ? – interrogating him, Ventura gives strange, possibly incoherent answers. Thus, it is decided: the old man must be hospitalized for his own good. Only this time it is not the Hospital de Santa Maria and the Hospital de Dona Estefânia realistically depicted in Costa’s Casa de Lava (1994) and Bones (1997) respectively, but more like an abstraction of foucauldian social-control institutions suspended between the hi-tech 2010s and the Middle Ages. It is a modern clinic, a Bedlam-like mental asylum, a morgue, a hunted castle, a penal colony, a catacomb, a police station and a fortress, all in one. Here, the tragic irony, highlighted by the black-and-white-striped pajamas worn by Ventura, lies in a geographic inversion: whereas the fascist and colonialist “Estado Novo” regime (1926-1974) used to send Portuguese political opponents and African freedom-fighters to the “slow death camp” of Tarrafal in Capo Verde, the democratic state born after the April 25th 1974 Carnation Revolution now puts Cape Verdean immigrants away in healthcare facilities in Portugal. “After all, isn’t politics a long, sordid procession of murder, torture, and treason? And today our dear revolution seems so far removed and unreal,” Costa recently stated[66][66] Ibidem. The already-mentioned original title for Colossal Youth – “Juventude Em Marcha” – is a Communist slogan used during the Carnation Revolution.. This was not said light-heartedly, as the filmmaker himself marched in the streets of Lisbon in his teenage years, right after April 25th 1974, joining left-wing rallies and shouting “Down with the Fascists,” “Death to Capitalism and Imperialism,” “United People Will Never Be Defeated” and “Portugal will not be another Chile.” But as the inebriation of the revolution led by Marxist-Leninist young soldiers gradually faded because of NATO pressures within the context of the Cold War, the ressaca – “the hangover of the morning after” – left nothing but broken dreams for the Portuguese people and the newly-independent, former Portuguese colonies in Africa.

By casting sixty-something Ventura to play twenty-year-old Ventura during Portugal’s revolutionary period (a temporal conundrum already used in Colossal Youth), and by having him wander between medieval and present-day Lisbon, Horse Money clearly shows that nothing has really changed for him and his people. Ventura emigrated to the Portuguese Empire’s capital city in August 1972 and, in spite of the 1974 Carnation Revolution putting an end to 48 years of fascist dictatorship in Portugal and to hundreds of years of Portuguese colonial rule in Africa, he kept on working as a slave, building rich people’s banks and museums in Lisbon for a ridiculous salary, and living in the clandestine slum of Fontainhas until the late 1990s.

The slaves from Howard Hawks’s historical fantasy Land of the Pharaohs (1955), an all-time cult favorite of Costa’s, were lucky enough to be granted freedom after laboring for years to build megalomaniac Pharaoh Khufu’s mausoleum. The same cannot be said for immigrants like Ventura: the Carnation Revolution never kept its promise of wiping out the exploitation of man by man, and Cape Verdeans are still captive in a foreign land, building today’s Great Pyramids all over Portugal, and falling (or jumping) from the scaffolds to their death more often than not.

Evidently, Costa has plenty of regrets and recriminations connected to the Carnation Revolution, and in Horse Money his broken dreams of youth meet those of the colossal immigrant from Capo Verde, and turn into nightmares. In the film, though, the focus primarily remains on Ventura’s. For instance, a giant black bird haunts his sleep, probably one of the vultures that tore his horse Dinheiro [Money] apart back in his native island. Moreover, everyone Ventura meets during his wandering through dark corridors and down spiral staircases might be a ghost, including Lento, the guy who might or might not be Ventura’s hallucinated younger self in Colossal Youth, and who might or might not die on two different occasions in that film.

Finally, after confronting the most frightening memory from his youth in an elevator, Ventura leaves the hospital seemingly reinvigorated, and goes to buy a knife in the streets of 1970s Lisbon. Is it because he needs a weapon to protect himself, in case his inner demons run amok again? Or is it because the nightmarish loop of bad memories has started once again, and Ventura is about to re-live the knife fight with a fellow-immigrant that left him half-dead on March 11th 1975? Or is it because Horse Money begins by showing some Jacob Riis pictures from the book How the Other Half Lives and hence must end with a hint to one of the last chapter of said book, “The Man with the Knife,” in which a poor devil assaults a random guy downtown as a desperate gesture of rebellion against the system? All are equally possible.

Surely, by the end of Horse Money, the time for marching is over. Ventura’s people are exhausted and on the verge of extinction : forced out of their native land since the early days of the Atlantic slave trade, now they are also denied their second homeland in Portugal – their shack in Fontainhas – and sent to end their days in damp white cubicles they hate, each one plunged in his own night, each day more silent, each day more lost. In the process, some died, some committed suicide, some were committed to Portuguese prisons or asylums, some were repatriated to the volcanic wasteland of Capo Verde. Given the clinical system of oppression and extermination the people of Fontainhas have been enduring, the man with the knife in the last shot of Horse Money reintroduces the question posed by the title of a 1975 João César Monteiro documentary about the struggle of the oppressed in the aftermath of the Carnation Revolution: “What will I do with this blade?”