Ben Rivers

Film Strata (V.O)

Last week saw the conclusion of the long retrospective that the Jeu de Paume devoted to British filmmaker Ben Rivers (born in Somerset in 1972). Curated by Antoine Thirion, the retrospective—forty films divided into thirteen programs, spanning nine days—was an opportunity to show in France many of the films that have been shown only within the film festival circuit and to give an overview of Rivers’ vast and varied filmography, which includes science fiction, experimental ethnography, found footage films, and variations on the tropes of horror cinema. The event coincides with the release of a book—Collected Stories, published by Fireflies Press—and a blu-ray—Worlds: Selected Works by Ben Rivers, published by Second Run. Collected Stories is a collection of fourteen texts Rivers commissioned to authors dear to him, whom he asked to write a text in response to one of his films. The collection proposes fiction and essay, echoing the mixture of fiction and documentary proposed by the retrospective. Rivers and Thirion used Collected Stories as a device to punctuate the retrospective at the Jeu de Paume: each session is an opportunity to invite one of these authors to read their text at the opening of the screening. I had the opportunity to speak with Ben Rivers in the aftermath of the opening of the retrospective.

Débordements: Yesterday, at the opening of the retrospective, you pointed out some sort of lineage tracing What Means Something [2015] back to Margaret Tait’s film A Portrait of Ga [1952]. Would you like to explain?

Ben Rivers: I think it’s definitely a lineage, because it actually goes back to when I was at art school. I’d only seen feature films, and luckily this filmmaker would come two or three times a semester and show us films from the London Film-Makers’ Co-op archive. And some of them I really didn’t connect with, but one of the first films I really connected with and sort of blew my mind was Margaret Tait’s Aerial [1974]. I’d never seen anything like it. It’s poetic, non-narrative, the sound is completely asynchronous. It was just a real discovery that that was even a possibility.

D.: And it is also a very good example of film as a gesture, a gesture that may seem simple, but you have to get to that and carry it out.

B. R.: It seems simple, but then, of course, it’s a film you can watch many times over. Many of Tait’s films you can watch over and over again. So a bit later, I discovered A Portrait of Ga, and I couldn’t tell you how many times I’ve seen that film. And within four minutes, she encapsulates this person and her feelings about this person [Margaret Tait’s mother]. And some beautiful little details, and a poem, and different weather…

D.: Also the end of the film: with the credits and the voiceover continuing, which was probably daring for the time.

B. R.: Yes.

D.: Who is the filmmaker who used to come and show you the films in art school?

B. R.: Nick Collins.

D.: Oh, Nick Collins! A filmmaker capable of making beautiful films with simple gestures.

B.R.: I’ve got a lot to thank him for, really, for showing me Margaret Tait and a few other people, like Kenneth Anger. I don’t really like the term experimental film, but let’s call it that, or artist film, whatever. But there was a certain kind which I really associated with, and I think it was films which still had some element of narrative. The abstract stuff I could be amazed by, but I felt little connection to it. And I think that’s because I still had a real strong love for narrative and seeing humans doing stuff. But I also knew I didn’t want to be tied to a kind of strict plot type of narrative. And this is what filmmakers that were really key for me early on, like Margaret Tait, George Kuchar, or Derek Jarman, do so well. Nick was very encouraging. I did fine art, there was no film tuition or anything, apart from when Nick came down for a few days.

D.: Was this some kind of workshop?

B. R.: Not really a workshop. He just did tutorials and then would do these screenings. I bought a Super8 camera and began to teach myself how to make films with that, and made my first film at art school. It was really after university, when I stayed in touch with him and we became friends that I think he might have shown me how to use a Bolex camera. Going back to lineage, when I was hanging out with Rose Wylie [protagonist of the film What Means Something], I didn’t think I could make anything as perfect as A Portrait of Ga. I simply thought, I want to commit this person and our friendship to film. So, you know, A Portrait of Ga was an obvious point of inspiration for that. But then, because I’m not trying to copy Margaret Tait, obviously, it turned into something completely different.

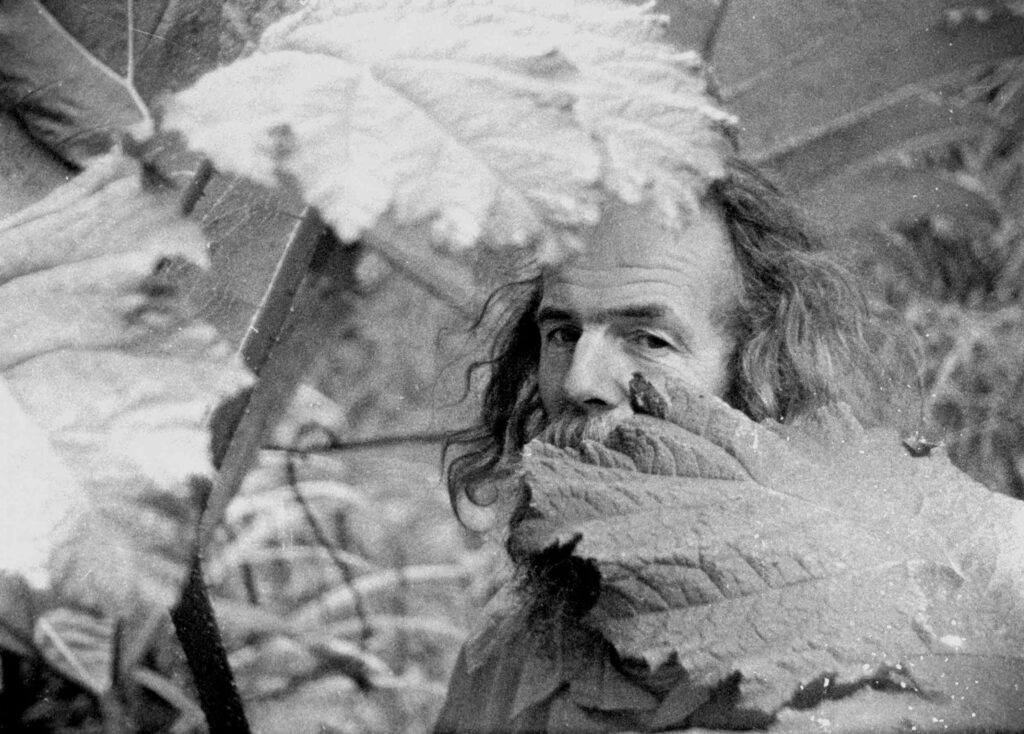

D.: In your filmography there is a sort of tension between the end of the world and the cosmos. Films like This Is My Land [2006], Astika [2006] and Origin of the Species [2008] are portraits of men living in the wilderness. But you also make use of creation stories, like in The Creation As We Saw It [2012]. Now, after more than a decade, you announced the sequel of Two Years At Sea [2011], entitled Bogancloch. I wonder if you’re going to explore even further this relationship between wilderness and cosmos with this new feature film.

B. R.: I suppose I like the idea of going back to basics. And when thinking about someone like Jake Williams in Two Years At Sea, even though he’s very much living in the present and he’s up to date on everything, people sometimes would say ‘It seems like he’s living in another time’ suggesting the past. But I always thought of him as being in the future, and it’s a little bit like starting again, but kind of reusing some of the leftovers of our civilization. But in terms of thinking about him in relation to the cosmos: there actually is cosmos in this new film, in a couple of funny, unexpected ways. I think the film is sort of bookended by the universe. I won’t explain how as I’m still editing.

D.: That’s going back to basics for you?

B. R.: Yeah, it’s kind of basic. Well, basic is not the right word. It’s a fascination for me about time, about the beginnings of things, the beginning of life on Earth, the stories in the rocks, and then the first humans, and humans having the idea to represent themselves and then that coming through all the way to 2023, where we still want to represent ourselves in some way, or make images of ourselves. However many times things collapse and go through these cycles, there’s still this very basic sort of need or desire to look back at ourselves.

D.: It’s interesting that people need to define timewise where the subject that is filmed lives. You say that your subjects, like Jake, live in the future, or in the present. What about you? When you’re editing your films, you’re working with the past. You have some sort of close relationship with the past more than Jake.

B. R.: Yeah, that’s definitely the case. That’s more the immediate past. I guess I’ve always strived to try not to make my films too time-specific, so that they kind of slip, so that the past becomes the future, the future becomes the present, and all the other permutations that that could be.

D.: A whole part of your filmography is composed of portraits of people, with whom you established an intimate relationship beyond the purpose of making a film. Some of these people are no longer with us. What is your relationship with loss, and in particular the loss of the people you have portrayed in your films?

B. R.: The same way that most of us deal with loss. With the difference that for Oleg, who’s in A World Rattled of Habit [2008], who was a friend—and his son too—it was really beautiful because we showed the film at the funeral and everyone was laughing and I felt really good about having made this record of this person who was really special. And it’s never meant to be a conclusive record. I don’t believe in the idea that you can represent someone anywhere near fully. That’s why my films never claim to be accurate documentaries, why I always try to bring in fiction, for me it’s impossible otherwise. There needs to be this understanding that this is a creation, a construction. And so that applies even to A World Rattled of Habit, which is probably a bit more straightforward because it’s just me going to visit for the weekend and filming him and his son getting up to stuff. But that’s a little different to this other film I made, Phantoms of a Libertine [2012], in which the protagonist, Bob, had been my friend for twenty years. And I’d always thought I wanted to make a film with him because he was a great raconteur, but I didn’t get round to it. And then he died, and I had to deal with all of his stuff in his flat. He had so much stuff. He was eighty-something and had accumulated lots of objects and books, and also he was a research librarian for Time-Life Magazine. So he had all these photographs and magazines that he’d worked on. And I went there for about a year, trying to sort out, kept going back to his flat, and I was finding it really hard to deal with his stuff. If you’ve ever had to deal with a dead person’s stuff, someone that you’d loved, you know it’s really hard. And eventually I decided to try and make a film. So that’s how that film happened: filming these images that he collected and trying to make kind of a post-mortem portrait by just offering clues to his life. In the end, I really like that idea that you could never really know someone fully, but you could just offer these clues of a personality.

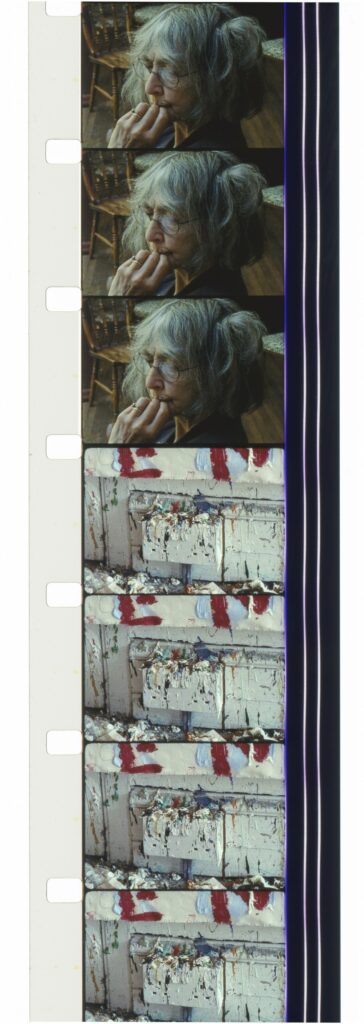

D.: Speaking of clues and portraits, I would like to turn the subject around and ask you to tell me about a short film of yours, Things [2014], which seems to be one of the few films of yours where you use, in a very free and abstract way, the self-portrait form.

B. R.: Yeah, I had Phantoms of a Libertine in mind when I made Things. I’d made this film about somebody else, and in the end, I liked the result. I could also totally clear out the flat after I’d made it, which was helpful. And so with Things, it was actually a kind of challenge from a curator friend, Gareth Evans. He asked me, a poet [Lavinia Greenlaw], a writer [Jay Griffiths] and a sound artist [Jem Finer] who all make work away from home, we were known for travelling a lot and making things elsewhere, not in London. So he set this challenge to make something at home. The project was called Stay Where You Are. I’d been living in this flat in Bethnal Green for about eight years. So I just took that as my starting point. The two things of the brief were: do something in London and do it over the seasons, in four parts. So then I set myself some rules, like: I wouldn’t shoot more than ten minutes every season. I wasn’t deliberately trying to make a self-portrait or anything. I wanted to more instinctually pick out things which I’d gathered around me, try not to question it too much—which is hard, because obviously it’s quite hard to turn off the questions. But I started very simply, I thought ‘OK, winter. I’m starting in the winter.’ So that’s, I guess, more of a time of looking back: you’re inside, it’s cosy, reflective, you look at the actual things that you’ve got. So I did what I had done with Phantoms of a Libertine and looked at images, and sounds, that I’d collected. Things that we collect and somehow they’re meaningful to us.

D.: Can you tell me something about the last sequence of the film?

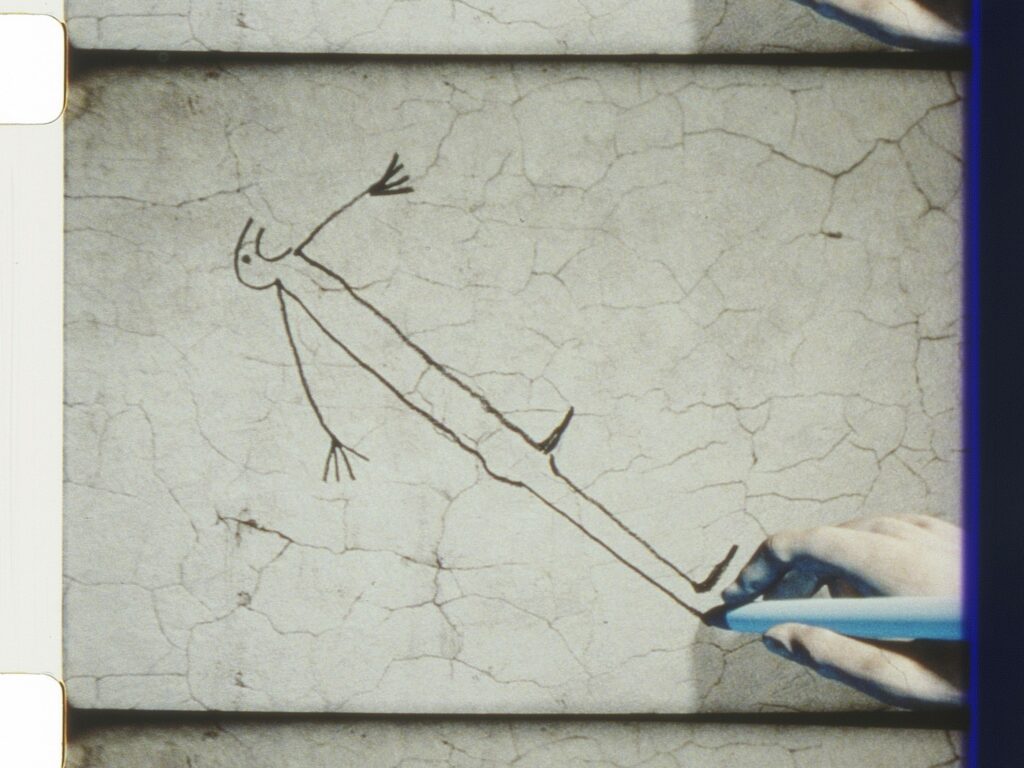

B. R.: So the winter was looking backwards. Spring and summer were more in the present. Things that I was actually looking at or reading or listening to at that time. And then autumn was the future. Thinking forward to my apartment in I’m not sure how many years, and imagining it as this place that I was stuck in permanently and couldn’t get out. And it was inspired by this video game I used to play called Silent Hill. There’s a scene in Silent Hill where you’re stuck in a hotel room and you have to find your way out. The walls are cracking. And you know that things are not good outside either, but you still need to find your way out. But then in the end, I don’t find my way out. I think, well, this is my cave, so I’m going to stay and do this drawing of the first figure on the wall.

D.: I have a quote here about Things, it’s by Dutch filmmaker Bram Ruiter: ‘The best quarantine self-portrait was made 6 years before the pandemic hit.’

B. R.: Well, the last sequence feels like a premonition in a way, doesn’t it? That was the theme. It’s funny because during the whole pandemic, people said to me ‘It’s the perfect time for you to make a film about this.’ And the whole time I was just like: I don’t want to make a film. It was the first time in years that I actually took a break, and went to the countryside to read, walk and think about films I wanted to make, but actually I didn’t want to film.

D.: What about the drawing that bookends Things and that is also on the cover of Collected Stories?

B. R.: It’s from Lascaux, it’s one of the first images of a human, the bird man, because he has the head of a bird. I love this idea that from very early on, people had this idea to create art, and the idea of wanting to show the world in another way so that it’s not just experience. You can hold on to that experience through an image, which obviously relates entirely to filmmaking. And the idea of the cave, Plato’s Cave. Those things have just been recurring in my films in different ways throughout. Even one of my earliest films, Old Dark House [2003], it’s not that far from Plato’s Cave: using a torch to reveal the space. Also, going back to what we said earlier about the cosmos and time: I guess for me, it’s interesting to try and make films which can exist beyond this moment, that they might make sense in a hundred years time or longer. Because I feel like, especially at the moment, we live in a particular time where there’s so much emphasis put on the idea of relevance, and I think it’s restrictive.

D.: By relevance do you mean contemporary relevance? The current?

B. R.: Current, current, current. And that also applies to technology as well.

D.: A portrait of an old person living in the wilderness can be current.

B. R.: Of course. It can be totally current. I think it makes a lot of sense, actually, and I think that it’s brutal.

D.: It seems to me that many of your films—the portraits of men in the wilderness, but also the ones that play like dystopias—make a lot more sense now than they did ten or fifteen years ago, they are much more striking today, now that we are finally talking about climate change.

B. R.: Yeah, I agree. I mean, I think a film like Slow Action [2010] is. It makes a lot of sense now.

D.: In your films you expose, in a very subtle way, the false dichotomy between documentary and fiction. Or rather, the porosity between recording an environment and creating it. Do you think your approach to this false dichotomy has changed after all these years of practice?

B. R.: I don’t know if it’s actually changed that much, because I think I always had suspicions about documentary and how equally manipulative it could be in relation to fiction. And a lot of the filmmakers that I’ve liked and have inspired me have made that very clear pretty early on, all the way back to Humphrey Jennings. It’s not a new idea. Maybe I’ve found different ways to navigate it and they’ve become more nuanced and complex as I’ve honed my tools. The first few films I made were without people. And I think that was partly because I was kind of tiptoeing in. After ten years of being a programmer, my brain being so full of everybody else’s films, I started very carefully, just me and my camera, making films of spaces. And then the first film with people—The Coming Race [2006], with thousands of people on a mountain—even then, they’re really far away. And then I think: ‘OK, now I need to get close to somebody’. And that’s when I found Jake Williams in 2005, thanks to a friend. I had no idea what the film was going to be, I thought I’d just go and spend time with him, take some rolls of film and see what happens. And so in that first film [This Is My Land, 2006], I’m still standing back a bit and filming him doing his thing. I’m not asking him to do anything. It’s a pretty observational film, but it becomes something else in the edit because it’s fragmentary, the sound is almost always asynchronous. And that’s what kind of starts to break apart this idea of accurate observation. I think it’s the sound that’s starting to fictionalise the space. And then over time and over films, I gained more confidence, more confidence to also talk to the person in the film about how I wanted to change it and how I wanted to not make something that their friends would necessarily recognise as themselves. So it’s also about conversation and finding the right people as well. I met people that I realised quite quickly that that relationship wouldn’t work and there was not a film to be made.

D.: And you didn’t?

B. R.: And I didn’t. I’ve never made a film where I felt uncomfortable with the person. That’s been quite important to me. And then, of course, I show people I’ve worked with the finished films as well, and luckily they’ve always been happy.

D.: Besides making films, very early on you also started showing films, programming films in a cinema.

B. R.: I made my first film when I was at art school, when I was a teenager in 1993. And I sort of knew that I wanted to make films, but I also loved showing films as well. So then I moved to Brighton and started a cinema with some friends and did that for ten years, pretty much. During that time I didn’t really make much. I made one or two films very slowly, and then gradually got more and more frustrated that I was just showing other people’s films and not making my own. And then it became like a coiled spring just waiting to burst.

D.: What kind of cinema were you into? Were you already into artist cinema?

B. R.: Initially, when I was a kid, I really liked horror films and noir and sci-fi, these were my main favourites. So I went to art school initially because I thought I’d wanted to make special effects for horror movies. I thought this would be a good way to do that. But then, of course, you go to art school and you’re introduced to all this other amazing stuff. Because I grew up in a cultural backwater in the countryside. There’s nothing there. Even though my mum had tried to show me stuff, there were limits to what was available to see. But art school was an amazing place to discover all these other things, other forms. At art school I still started running a film club, which was mostly historical cinema. And then with the cinema in Brighton, the whole ethos of it was to never be tied to a particular type of cinema. Everything was valid, really, from Méliès and the Lumière brothers, George Kuchar of course, John Waters, Bruce LaBruce, Paul Verhoeven, films from all over the world. Really everything, all the different shapes and colours of cinema all over the world. It was really like a mishmash, and one of my main sources was Film as a Subversive Art by Amos Vogel.

D.: What type of audience did you have? Fellow students?

B. R.: When I was running a film club at art school, art students were kind of annoying because everyone just wanted to go to the pub every night instead of going to see my weird film screenings. So I’d go around the studios trying to persuade people to come. And then at the Cinematheque in Brighton, some people were students. It’s kind of an arty town and people like music and experimental stuff, so I think the audience would change. We’d show some American transgressive cinema and you’d get a cinema full of people wearing black leather. And then you’d show a silent movie and you maybe get an older generation. So it wasn’t one particular group, which was also nice.

D.: So the curatorial practice has always been there.

B. R.: Yes, it’s always been there. Making films is so inseparable from my life, also watching them. It’s very hard for me to have a kind of work-life divide, everything is so intertwined. And I’m definitely not one of those filmmakers who’s only interested in their own work. I still really like watching other people’s films, new and old. I miss running the cinema, even though it really had to end. I mean, it became too much, really. It takes up so much time running a cinema. But I always wanted to try and still have a hand in showing other people’s work in different ways. So if I get an invitation for a show, if they’ve got a cinema in that museum, then I’ll try and do a series of other people’s work. When me and Ben Russell were making A Spell To Ward Off The Darkness [2014], we curated a really big programme for CPH:DOX, with tons of films and music performances, that had fed in some way into our thinking about the film.

D.: Collected Stories, this collection of short stories you commissioned, also seems to be part of your curatorial practice.

B. R.: I’m reading all the time. I love reading. To the outside world, it’s always been about cinema, but for me personally, reading is equally important. So this book and having the writers read here at the retrospective is a really nice way to show that side of my work and life.

D.: You co-curate at the ICA the film club The Machine That Kills Bad People with Erika Balsom, Beatrice Gibson and María Palacios Cruz.

B. R.: It’s about finding an excuse to spend time with people that you like, about gathering a community. So with The Machine That Kills Bad People I’m doing that with three really close friends who I love. We just hang out every month or two and we have a meal and we talk about what films we could show over the next few months. But then the screenings as well, it’s about community and talking. It’s not enough, for me at least, to just sit at home and watch things by myself. So I think that’s a really big part of it as well. The Machine That Kills Bad People has been a success, we get good audiences, it feels nice. Cinema is alive.