Deborah Stratman (V.O.)

Object Lessons

Last April, Débordements met U.S. artist and filmmaker Deborah Stratman in the context of her invitation by the Jeu de Paume in Paris for a retrospective of her film work curated by Antoine Thirion. Her last short film, Otherhood, had just been shown a week before during her carte blanche in Cinéma du réel, alongside other films from Maya Deren and Barbara Hammer.

Débordements: In The BLVD (1999), the act of filming is often pointed at by the people being filmed, which gradually leads to the last part of the film, an almost self-reflexive sequence which documents the act of filming drag races. At one point you film another person’s camera viewfinder. That very image seems to me paradigmatic of a way you construct your films: you look for a physical way of entering a new stage of vision—I’m also thinking of the central scene in For the Time Being (2021) where you film the crater through a tourist telescope. How would you define this aspect of your work?

Deborah Stratman: The edge of the frame and the edge of the story interest me. Where does index end and story begin? Where does the person end and the character begin? Where’s the frontier between myth and document? I think what you’re pointing to is a cinematic interest in the edges or “the wings” of the stage, where the scripted meets the accidental. Even when you’re making documentary without actors, every person in front of the camera is playing a version of themselves because their consciousness of the camera means the future is in the room. And if you know the future is in the room, you change. The camera always changes the fabric of reality. I like when people are conscious of that and play to it. But we mostly do it unconsciously. I do it right now, I’m playing a version of myself to you. When and how we shift in those roles is interesting to me. Sometimes it’s easier to catch those shifts through framing because that is the most consistent element of cinema, you can’t escape the container of the frame. But you can pull back and reveal an edge, or zoom in to someone else’s frame—like you’re describing, in the viewfinder—see someone else’s apparatus, shoot another monitor…

Hacked Circuit (2014) is an example where edge-consciousness happens both visually and sonically. The place where something ends tells us something about what it is or was. And this focus extends into my framing habits. With Hacked Circuit the edges are multiple—like nesting matryoshka dolls. It’s a structural form that can serve audiences on many levels, depending on whether they’re familiar with the films being cited, or the art of foley, or the neighborhood where the studio is located. The objects which the foley artist uses are nested too, in the sense that each has a more common ‘use identity’, as well as a sonic ‘use identity’. An aluminum window blind is alternately a clattering metallic cascade.

I like the way the texture of an image changes when shooting an image of an image. It makes us conscious the apparatus. In the case of The BLVD, you start to see so many other people with cameras in the act of capture that by the end, shooting becomes more of a shared network instead of an assumed power. Right from the beginning, it’s like, ‘What is that? A VCR?’ There’s curiosity about the tool. You see shadows of cameras being passed between people. It’s a subject too. Or maybe a companion.

D: Throughout the film, we also see people getting to know the camera, acknowledging it on a technical level. As you said, Tim asks you if it’s a VCR camera. We don’t see or hear much of the conversation between him and you about this, but we understand that you showed him that it’s a digital camera and what are some of the features of the object, like seeing the live preview in color. It’s a small narrative underneath this ethnographic film.

D. S.: A narrative of the act of viewing. It’s just another thread of the theatrical, because clearly, they’re performers and the stage is the street. And when they’re notracing—which is most of the time—they are performing stories for one another. The scene is all about storytelling and trash talking and who’s good at it. Tim is a master storyteller, but so are a lot of people there. When I first showed the film to the racers, that was their main complaint: ‘There’s so much talking! Where’s all the races?’ I said, ‘Dude, that’s what you normally do. You guys are just talking all the time. 1% of the time the race happens, but the rest of the time, you’re either getting chased by police, or you’re finding a location, or you’re measuring it out, or you’re fighting about how much the bet is, or you’re playing cards, or you’re telling stories. That’s most of what you do. I’m just trying to capture it.’ So, they said ‘Oh, okay. But you should have more racing.’ I think that’s why so many of them started filming, because they were frustrated with my style. — ‘Why aren’t you focusing on the important part? —I’m like: ‘Well, that’s your story to tell’.

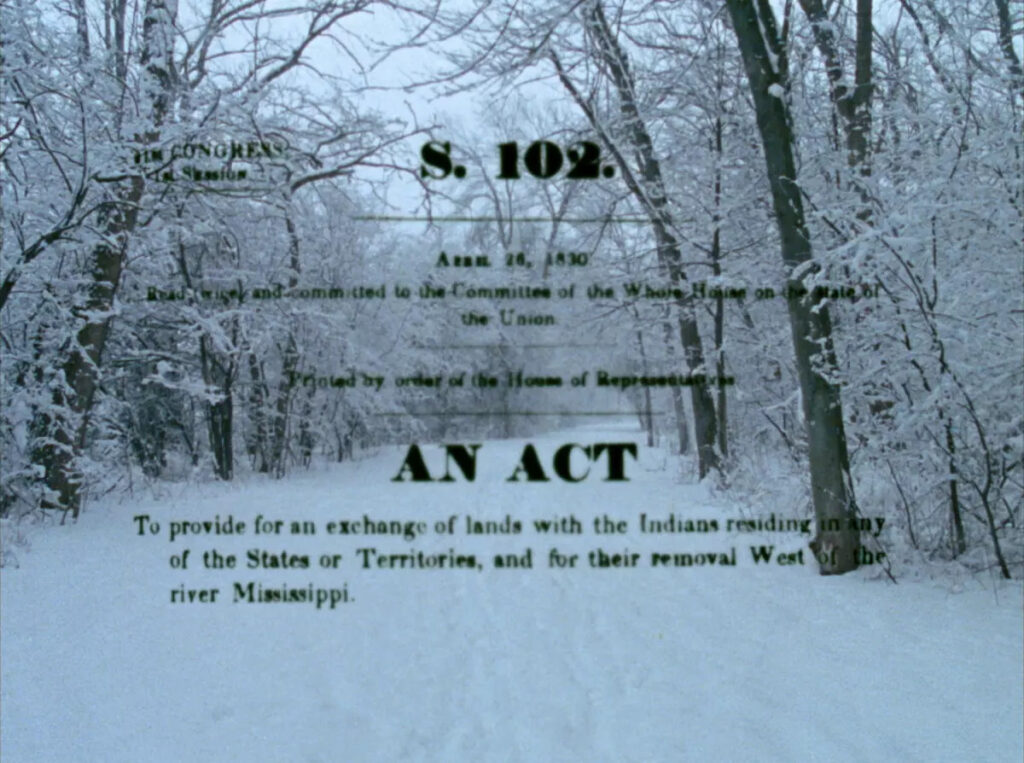

D.: In an interview with Tenk, you talked about Last Things (2023) as a film made from a ‘science and science fiction’ perspective. But maybe we should add that you also find a lot in the archeological past of modern sciences. In many of your films you use the speculative inventiveness of the late medieval-early modern era as a creative matter. In …These Blazeing Starrs! (2011), for example, you use engravings from a book written by the Calvinist poet Guillaume du Bartas, author of an anti-Copernican and geocentric cosmogony, La Sepmaine (1578), which re-enacts the biblical Genesis and intersperses it with references to the pagan poetic tradition. In parallel, the book’s engravings are edited with images from NASA. What do you want to emphasize by obscuring the stories of modern and contemporary science?

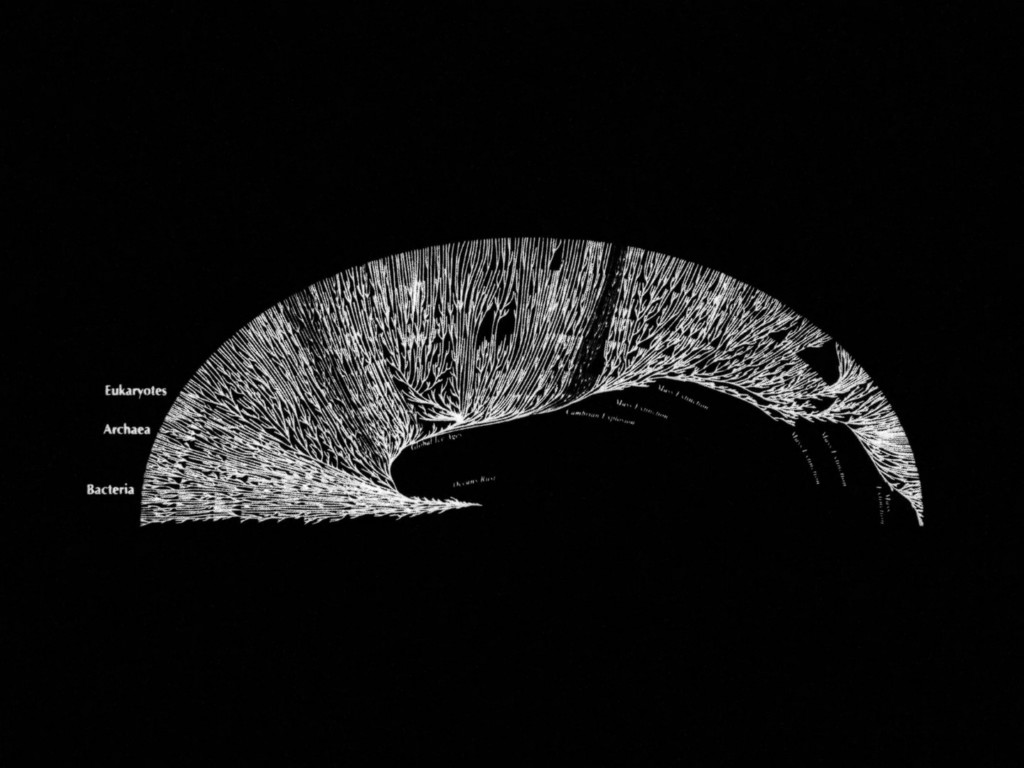

D. S.: It’s true a number of my films—From Hetty to Nancy (1997), …These Blazeing Starrs!, certainly Last Things, and On the Various Nature of Things (1995), which uses Michael Faraday’s physics lectures—all of them stir together a poetics with a logics. In Last Things, I think of it as geo-poetry, but I have different names for it in different projects. In these films the metaphysical sits down with hard science. I’m not advocating we revert to oracular, speculative modes at the expense of the empirical. I don’t want to obscure modern science. But Western science’s exclusion of abstract, unpractical, lurching poetics truncates our ability to think in ways that are necessary to live and be among.

In what ways do we reach towards the unknown? When faced with something you don’t know, what strategy do you deploy? Today’s science is so data and profit driven. So much ugliness and suffering happen in the name of progress. It’s not that I think that insisting on the metaphysical solves the problem. But a lot of people in the Western world feel adrift. We miss… something. We’re looking for a new shared narrative, a new communal story.

There are quotes from Tarkovsky’s Stalker (1979), who was himself quoting Dostoyevsky, in my film It Will Die Out in The Mind (2006). He says, ‘it was interesting to live in the Middle Ages when each house had a Goblin, and each church had a God.’ Dark unknowns and ecstasies were woven into everyday life. They were part of a common belief system. Of course, a lot of people still have faith today, including some very narrow adaptations that keep them from thinking at all. But there’s a lot of post-religion folks left wondering what fills that hole? Is it poetry? Is it art? An unorganized spirituality? Activism? If people feel unmoored and existentially depressed about the ecological state of the planet, or the monstrous things humans do to one another, where do they go for solace? I don’t know. But it’s why I keep inviting the metaphysical to be in conversation with the rational. They reveal one another’s poverties and biases.

In his incredible essay L’intrus (2000), Jean-Luc Nancy wrote about having a heart transplant. He describes how we react not only to what comes into your own body, but what comes into our culture. When migrants and displaced people arrive, there’s often a push to assimilate, so you no longer recognize that they’re ‘Other’. Nancy suggests instead we should learn how to bring the alien into our body and let it remain alien, be an intruder yet still be part of the community. This is how I want rationality to exist: as a neighbor to the metaphysical, without assimilating one another. I think they can throw each other into relief and make philosophical, ethical thought possible.

D. : Let’s continue on this thread on 16th century French writers since you seem to have a soft spot for them. How Among the Frozen Words (2005) is a very short film, but it occupies an important place in your filmography, opening the cycle of the Paranormal Trilogy (2005-2007). The film draws on one of Pantagruel’s adventures in the Quart Livre (1552) called the myth of ‘frozen words’ [parolles gelées in Middle French], reconsidered by many as a precursor of aesthetic communication between words and images. In your film, there is always a tension between the literary tradition—quotes are abundant: the Boex Brothers, Clarice Lispector or Roger Caillois in Last Things; Tocqueville and Emerson in The Illinois Parables (2016), etc.—and the history of experimental cinema: the colorful fireworks of the frozen words melting in Pantagruel’s hand evoke the colors of the crystals in Last Things; Optimism (2018)seems to allude to the reactivation of the coils found in Dawson City: Frozen Time (2016) by Bill Morrison, etc. How do you combine these two traditions, the literary and the experimental?

D. S.: I love this idea of the mute world—or the seemingly mute world—containing time and having stories frozen within. Rabelais seems to be writing about tape recorders and record players hundreds of years before they were invented. The leap of imagination it took to think ‘Why couldn’t this apparently inert piece of matter contain another time?’ is great. Maybe the technology of stored time releasable from a piece of matter was always there, just waiting to be invented.

I’m a reader. Reading was one of my first loves in terms of how I related to the world, and I like texts that come from outside my own time or culture or social context, texts that help me think outside our current decade, our current century, even, or millennia. It’s why the writing of minerals and rocks became compelling to me: they’re a text that exists outside my frame. When I was shooting From Hetty to Nancy I spent a lot of time with geologists, touring Iceland. I was blown away by how everywhere we were, they could just look at the cliff and read it. Maybe that was when the idea started about: ‘Wow, people are literally reading the land as text. What are the other ways? What are other texts that aren’t sentences? What are other forms of writing that aren’t necessarily words?’

In a film like The Illinois Parables, I thought about cultures that built mounds. That’s a history written on the land. Or the way a tornado passes over and erases a path. That’s a writing too. Language is often central, but I’m trying to think beyond pen and pencil and paper and typewriter. What other forms of language have stories to tell, are speaking already, but we’re not listening? Or maybe you’re listening if you’re a geologist, or if you’re someone who studies tornado paths, or if you’re an archeologist. I don’t speak a lot of languages. I speak a little German. I learned a little Laotian. A little Latvian. A little Icelandic. For the most part, I forgot them all and I’m stuck in English, but I do speak cinema. It’s a language that’s indigenous to me. I want to make cinema that can’t be translated into sentences; where sentences are insufficient to the ideas the film is speaking. I mostly don’t succeed, but when a sequence is convincing, it’s because this untranslatability is at play. There’s an intellectual pleasure that can’t be translated into words.

D.: Let’s talk about another type of writing: editing. Let’s talk about the way you use figures to think about the footage you’re going to edit. For example, the loop figure, and how you use it in films like Village, silenced (2012) or Hacked Circuit (2014), you use the concept of looping in different ways. It seems to me that the goal is never to reach its physical or pragmatic result: the goal is not looping the film you’re creating, but rather using the concept of loop as a means to think about the footage you’re editing.

D. S.: Yes, and it does change from project to project. With Hacked Circuit, the loop was central because it’s such a paranoid form. A loop evokes being stuck in a habit of thinking, getting more and more suspicious. Any entrenched thought loop can be a paranoid one or can lead to a paranoid one. In the case of Hacked Circuit, that return, and building on the return, getting more and more entrenched, it felt pertinent to the subject matter of what’s real and what’s not, who’s listening in, who’s surveilling, how much does someone else know? In the case of Village, silenced, I wasn’t thinking about paranoia or surveillance. It’s a simple exercise: if you use the same image and change the sound, what happens? It illuminates how differently we see depending on what we’re hearing. Both of those films are about the way sound controls and polices us. The big speaker on the car makes me think of all the other militarized uses of sound as camouflage, or for social control, or to misguide. Sound is Machiavellian and subversive. That’s why I’m interested in it. The loop was also instrumental to Immortal, Suspended (2013).

D.: Because of the scroll that you filmed.

D. S.: Yes. Maybe loop is the wrong word… but because it’s a single shot, like Hacked Circuit, the form becomes an interesting problem. What do you do when there’s no cut? How do you make meaning without that joint? I rely a lot on the site of the cut in most of my films. It produces something dimensional, it’s multiplicative, not additive. So I liked having to deal with this problem of… not exactly looping, but working with a more sinuous line, figuring out alternate ways to shift the viewer into a new dimension of thinking without a cut. You could turn a corner, or you can use the sound, you can use figures suddenly showing up. A form without cuts is related to the problem of what to do if you’re in a gallery and people can come and leave at any time. In the cinema, a film is like a chord. The distance between the first image and the last image sets up a particular resonating form, like the space between two notes. But if people can come in at any time, there’s no chord. How do you create tension? What other mechanism are you going to use to get things vibrating?

The loop question vis-a-vis a gallery experience is not one that I’ve problem-solved for cinematically yet, but I would like to. I’ve thought about the temporal problems of installation, but not specifically for film. Tactical Uses of a Belief in the Unseen (2010/2012) was a big, tessellated landscape, maybe twice the size of this room. You could walk on top of it, and the landscape itself was a speaker which played very low frequencies. You heard the sound through your feet, through the parts of your body that touched the ground, but not so much through your ears. That territorial sound was one of two compositions. The other played from a very directional type of speaker called HSS—Hypersonic Sound—through which sound doesn’t propagate in the normal way: it travels in a narrow beam. One person hears it and the person right next to them does not. That speaker was ceiling-mounted on a moving gimbal, so the sound occasionally hits you and then just as suddenly, goes away. When I was composing for that speaker, I had a similar problem to a loop, because you don’t know when someone will encounter the sound. So, I tried composing more vertically; thinking about which stacks of sounds are occurring at any given time. These sorts of structural problems shift with the project. I try to find solutions that aren’t too habitual to myself.

D.: During the retrospective opening’s Q&A, you used this expression: problem solving, when replying to Valérie Massadian’s [the French-speaking voice reading texts in Last Things] description of the way you work with sound. You said that sound for you is a subversive tool, that you trust sound as a problem-solver and a space-building tool. Could you give us a couple of examples? A moment of recording or editing sound that was game-changing for you.

D. S.: I think one angle I could talk about is how we are better equipped as listeners to hear density of content than we are to see density of content. There’s a density limit to both vision and sound. For instance, footsteps: you hear one person walking, you can discern the sound of two people walking, but once you have three or more, it starts to become a jumble, and you can’t differentiate. There’s a limit to the number of content threads you can be paying attention to at the same time, like music, ambience, and voice for instance. We can absorb more sonic layers, keep them distinct and still make meaning in a situation that, had it been only visual, would get jumbled.

There’s a scene in The Illinois Parables where you’ve been hearing some people give testimony about their memory of being in a massive tornado—the Tri-State tornado, which was a mile wide, two kilometers wide! You can hear through their voices from which part of the century they’re speaking. They don’t sound contemporary. Even though you never see them, you know a lot about them. You can hear that they’re slightly elderly people. You can hear what part of the state they’re from. You can tell because of the way they put sentences together. Through their idiom, and the grain of their voice, there’s already so much social information. One of these women tells a story of their house being destroyed and losing a favorite parrot. Her father later finds the parrot in the rubble, and it was singing the song Sweet Hour of Prayer. She stops speaking and the film cuts to footage taken from a biplane, old black and white aerial footage shot in 1925 of the destruction on the ground. Meanwhile, you begin to hear a song performed by a black gospel choir, The Lunenberg Travelers. They’re singing the same song the parrot was, but from a different cultural frame. The storyteller was an older white American lady, remembering the parrot’s song. The way she sings it is culturally different from the gospel choir, and temporally different as she’s impersonating and revoicing the parrot. The choir is inhabitingthe song, they’re emotionally in the present but technically in a past because we hear the song through and old, crackling record. We hear the presence of the archive, and we hear the past through the style of song interpretation. But we also hear the mourning of a history much longer and darker than the tornado. To me the African American voices are a sonic down-shift, going deeper and heavier. Sweet Hour of Prayer was a standard tune that many communities would have sung. There must be hundreds of versions of it. I chose this one because it moved me the most. Later in the same shot, layered on top of the choir, you start hearing a broadcast voice, a municipal warning that a tornado is near, that bridges and houses might be destroyed, that windows will be broken. So first you get the choir’s emotional register, and then with the broadcast, you get a governmental register. It’s more contemporary, though could be any time in the last 50 years—whereas The Lunenberg Travelers recording is lodged further back at the time of the event. Next you start hearing a third layer of sound, which is a father and daughter who are inside a house as a tornado arrives outside. It’s destroying their house and they’re stuck in the bathroom. These voices are distinctly of the present not just because they’re describing the event as it’s happening, but because the delivery mode registers as contemporary social media. They’re in the bathroom with a cell phone, recording live. You hear their panic, and the moaning and creaking and breaking of the house.

So, during this one sequence, you’re simultaneously in the present, in the recent past and the distant past, with multiple registers of emotional response, all distinct, not blurring into one another… and it never feels like too much. What I’m trying to say with this very long description is that if I tried to do that through the image, to pack in all that content via what you’re seeing, I don’t know how I would do it. It doesn’t seem possible. It would be some dense collage, or superimpositions and too overwhelming to take in visually. But sonically, we have no problem. This is what I love about sound, that you can have an extreme density of content, and it feels effortless, which is why people don’t pay as much attention to sound, because even though there’s tons of manipulation going on, we don’t struggle to make sense of it. I like that great sound design generally goes unnoticed. A lot of sound designers, at the peak of their art form, strive to be invisible, just like surveillance experts. There’re other times that I play with a lesson from Godard. He worked very simply through the whole first half of his career, with very few sound tracks. I love the way he’ll just radically cut all the sound out, add it back. He’s constantly revealing what he’s manipulating and then letting go of that and letting you flow with the film.

D.: Vertical editing.

D. S.: Yes, vertical editing, maybe I overuse the trick, but the power of what happens when you remove sound is strong. In O’er the Land (2009), I remove sound during the shot of a fighter jet flying overhead and continue the silence into the next shot of a body stepping off a bridge. Then I cut sound back in with an image shift to a group of people using flame throwers. The film is about freedom, and what we lose in the name of freedom. As it goes along, there are increasingly forceful representations of technology and militarism. The film starts with small, vernacular theaters of war which get bigger and bigger. There’s a voiceover at the center of the film of a pilot being forced to eject from his jet at high altitude. It’s an extremely visceral story. His body defies gravity because he gets caught in the up and downdrafts of a massive thunderstorm for 45 minutes. This story’s still lingering in your memory when you see, later in the film, the shot I mentioned of the jet. At first you also hear it, but then the sound drops away. I use silence to signal a philosophical core. Our American problem is that we define freedom in terms of ownership. The story of the pilot is a byproduct of defense technology, a narrative that equates freedom with ownership, that if you own things (personal property, or a nation-state) you need to defend them. But the guy who steps off the bridge chooses to drop, and this is very different sort of freedom: someone letting go of control, letting go of ownership, allowing something bigger than self to take over, in this case, gravity. That’s a real freedom. A transcendental freedom. This is a critical moment of the film, so I use silence. If there’s sound and suddenly not, it’s like a vacuum and your attention gets sucked in. It can’t help but be caught.

D.: You mentioned that stacking information is something that has to do with sound exclusively and couldn’t be achieved with images. Yet, as you mentioned just before, figures that come in front of the image are something you are using in your films all the time. Do you feel that visual and sonic materials are comparable to work with?

D. S.: I might have a synesthetic way of editing. I think there’s times where you see something, but remember it as a sound, or hear something, but remember it as an image. I cross them over a lot, and that comes out in my editing. I can’t edit pictures without sound, and I can’t edit sound without pictures. I won’t know how long a shot should be unless I have the sound. I won’t know how much I sound I should layer up unless I have the image. Sometimes the image is the shell, and the sound is the content, and sometimes vice versa. Laika (2021) is the one project I’ve edited where the sound was fixed, because it’s basically a music video. I could only change the image. But for me, usually that’s very strange.

D.: How do you describe your use of scientific figures in the context of stacking information? How does the abstract and scientific explanation of reality react to its layering onto a more documentary image, for instance in the film For the Time Being? I’m thinking of the dots that you’ve superimposed.

D. S.: Those dots are the holes Nancy Holt bored into her sculpture Sun Tunnels (1973-1976) that correspond to four different constellations. They’re a quotation of her sculpture. And it’s okay for me that they remain abstract. Or maybe you recognize them if you know Nancy’s work. It’s the same with my graphics, as you’ve mentioned—sometimes you may know exactly what they are, other times they’re an abstraction because you don’t know the context.

Why do I use those? I think it has something to do with being a curious viewer. I don’t like being over-oriented. I don’t like everything to be named. The Illinois Parables uses many different modes of representation: newspaper headlines, earthworks, photographs, graphics, testimony, reenactment, paintings. Each of these is a different modality of representing history. I’m interested in which we find more reliable, which ones we trust. In Optimism you see an atomic drawing of electron rings which is the molecular pattern for Gold. It’s fine with me if you don’t read it that way—it can just be a mandala. But if you do happen to know what molecular patterns are, then there’s an extra layer of meaning. I like that the graphic can either skew towards something mystical or oracular, or just be an illustration of an electron. It doesn’t matter to me which way your background prompts you to read it. It’s like with henges built by ancient peoples: we can’t know exactly what they were meant say, but clearly, they were saying something. How I interpret the stones of a henge depends on what I know about those cultures, or those religious systems, or how heavy rocks are. Or maybe I’m someone who studies lichens, so I’m interpreting what lichen growth patterns reveal on the rock surfaces. Henges communicate outside of their time even if we don’t know precisely what was being said. Monuments are temporal assertions. Henges are arranged habits of matter. They are vibrational patterns that communicate beyond normal language. With the graphics, or the henges, if their meaning is opaque, then they morph towards the magical. Other people have asked me ‘How do you draw the line between what’s opaque and what’s not?’ I don’t. I can’t draw it. That’s what makes the cinema belong to the audience. Each person draws a different line.

D.: The question about figures brings the question of pedagogy. Each film seems constructed as a form of lesson, but never an authoritarian one, they’re more like a ‘parable’ or an ‘object lesson’ [leçon de chose] than a scientific exhibition. This kind of lesson does not come from an overlooking position (typically: the voice over), but on the contrary from an interest in the frontality of the document (visual or written). Since you are also a teacher at the Art Institute of Chicago, we wanted to ask you what kind of pedagogy you defend in your films?

D. S.: I want to avoid being pedantic. I hate things that tell you how to think. It drives me crazy. Why are you making this for other people? It’s totalitarian. It’s not my interest. I think cinema is already totalitarian enough because it’s a kind of monologue. If you come to the cinema, you’re relinquishing your time in order to have some other time to infuse yours. This is already a vulnerable position. If on top of that, a filmmaker is also like ‘Now let me explain to you what we’re about to do, and what it means, and what you’re going to learn.’ Why? I want to give people tools to help them think, not to tell them what to think. When I’m teaching in class, the goal is to help the students (and myself) get better at articulating our questions. We’re all learning together. We help each other. Pedagogically, what interests me is how we co-produce society. I think we need to be in dialogue with one another, and it’s up to us to shift what society is.

D.: Speaking of pedagogy, many important contemporary filmmakers from the US have passed through CalArts, as students or teachers, including you, James Benning, Sharon Lockhart, Lee Anne Schmitt, Brigid McCaffrey… Would you say there is some common ground or at least a common modus operandi, beyond the use of 16 mm film?

D. S.: That’s true, all those people are (or were) filmy. I mean, I myself am 50/50: 50 digital, 50 film. Though my celluloid films are maybe better known. I would say James’ legacy is one of sight and landscape and embedding. He’s definitely someone from whom I learned to transplant soundtracks from other films; how to recontextualize previous writings and voices. I was a student there in the early ’90s, and the way he’s taught has shifted. More recently, he started doing those classes where you go out to a site, but you can’t bring a camera or a recorder, you just have to look and listen. I think that really impacted a lot of people. I don’t know if I can diagnose CalArts. You probably could do better as an outsider. What’s your take?

D.: Maybe CalArts gave you all a way to critically embed your work and yourself into the history of cinema and the genres of experimental film? With your films you have navigated through lots of genres of experimental film, but none is treated as pure. For example, you did a flicker film, FF (2010), using ethnographic material…

D. S.: Definitely, I think a sense of the political and the critical did blossom for me, for sure, when I was in grad school. My undergraduate experience was more structural, formal, more experimental. I think it was probably a combination of where I was in my life trajectory and what films I become exposed to in that period after undergrad, where the socio-political became more central. Was I always promiscuous with the genres? I’m not sure. Maybe the early films were more purely experimental, like My Alchemy (1990). With On the Various Nature Of Things I was already bringing in the lecture form through Faraday. And I was exploring what ‘gravitational’ could mean on both physical and psychological levels. The psycho-ecological is central to my cinema: where things slip between material, emotional and political registers. But some films aren’t so genre promiscuous. Sometimes they’re reactionary: each time I make a new film, it resists the style I previously used so I can work from a place I’m not too comfortable. That’s why I like the outside, the accidental outside, the real world. My problem with a lot of the experimental cinema I saw early on, as much as I loved it and recognized myself in it, was I felt like: Where is today? Where are the politics of today? Where’s history? Where’s the outside? How can I bring the outside in and still work with this poetics I feel at home in?