Prismatic Ground, 2022

New York (almost) by the Sea

Débordements did not cross the Atlantic Ocean to attend the second edition of Prismatic Ground and had to watch the experimental and avant-garde films of the festival from Paris, far from New York, Maysles Documentary Center, the Museum of the Moving Image, and Anthology Film Archives. Anyway, the oceanic feeling of the moving images and the waves (“wave” being also how the programmes are named), seas and fluids dancing on our screens managed to single-handedly get us off solid ground.

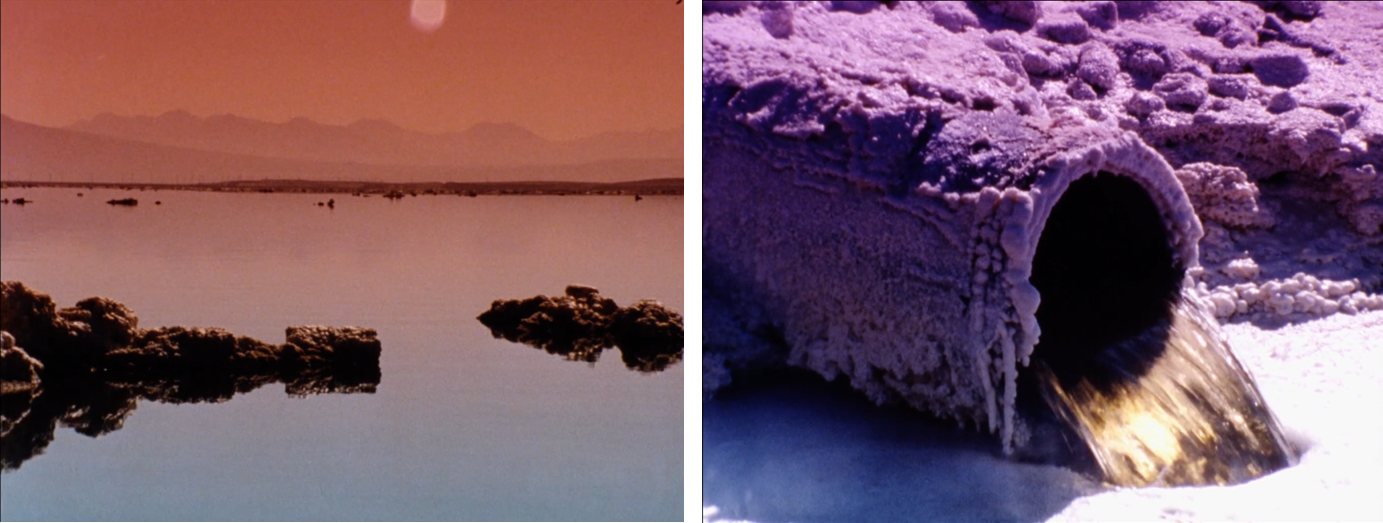

Highlight 1: open sky / open sea / open ground by Libertad Gills, Martín Baus, 16mm

Highlight 2: Instant Life by OJOBOCA, 16mm

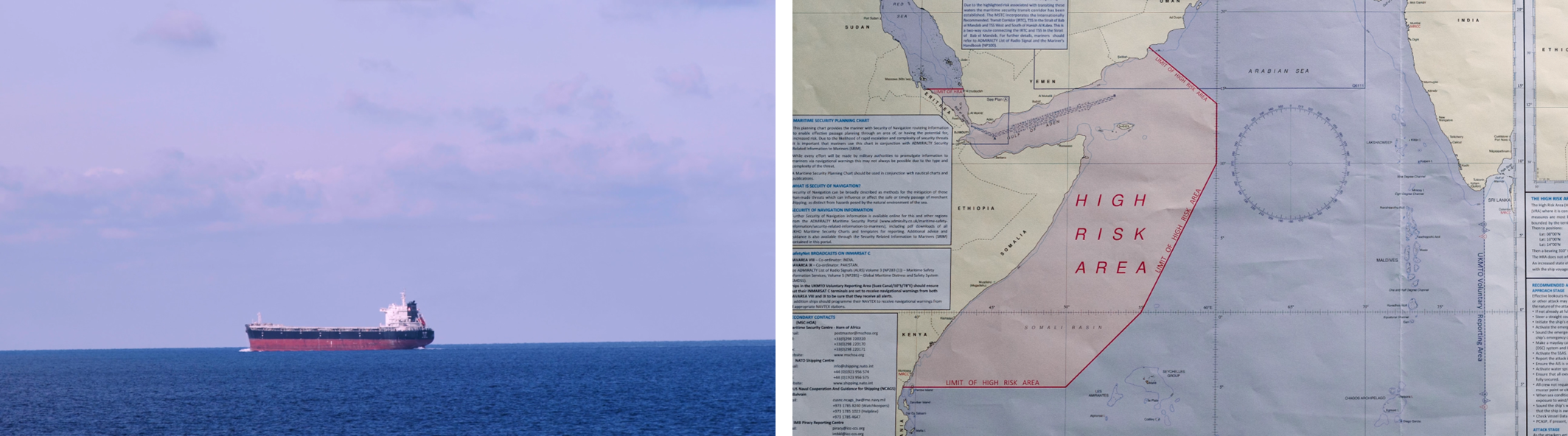

It’s a funny story, indeed, that first caught my ear when I started wandering among the moving images of the different programmes. The one told by Frank Heath in Last Will and Testament (Wave: Industrial Capitalism and the World) while showing images of the Suez Canal, both recounting the anthropological and historical lore of this tiny waterway and its region, and the destiny of this pharaonic enterprise in late capitalism. Heath’s will connects these two strange times: ancient mortuary traditions of burying the dead under roads to protect travelers and the symbol of the hubris in which globalization is rooted.

Frank Heath, Last Will and Testament, Digital

If you sail through the Suez Canal towards the Mediterranean Sea until you enter the Aegean Sea, you simply have to turn to starboard and sail through the Dardanelles Strait, across the Marmara Sea before reaching the Bosporus and the Black Sea. There, you’ll find some of the images included by Kamila Kuc in What We Shared (Wave: The Memory of a Memory), a film in which the artist uses the water as a screening surface (or an editing tool?) for the archive of the 1990s in Abkhazia she gathered. From the bubbling of these images and sounds she fed to an AI, new forms and ideas emerged, co-invented by the human and the artificial memory.

Kamila Kuc, What We Shared, Digital

“After months of total darkness” (since it is the name of the wave to which the film belongs) you shall be washed up on a new shore, somewhere in the Irish Sea, spit out by a White Hole – did you know that in physics, a white hole is the exact opposite of a black hole, meaning that no information gets into it, only gets out? In the film made by Eavan Aiken, named after this kind of singularity, this physical characteristic is translated by a luminous still shot on a cliff beaten by the sea spray, on which a seemingly infinite herd of cows passes, accompanied by jazz music and a text displayed between the rocks.

Eavan Aiken, White Hole, 35mm

Highlight 3: Self-portrait by Joële Walinga, CCTV

While light, words and music are generously delivered by Aiken’s white hole, another film takes on the Sysiphan task of illuminating the inside of a black hole. Arriving at Guantanamo by the bay, Katie Mathews & Jess Shane’s film that soberly announces its feature by its title, Signal and Noise, alternates images of empty cells and records of former prisoners (Wave: The Blessings of Liberty). Inspired by the Canadian poet Jordan Scott who recorded sound instead of images while he was invited to took the same tour as journalists invited to show the interior of the infamous prison, the artists uses the sound of voices, description of sounds as means of torture and recollections of the ocean breath as the only hopeful sound breaking into darkness.

Katie Mathews, Jess Shane, Signal and Noise, Digital

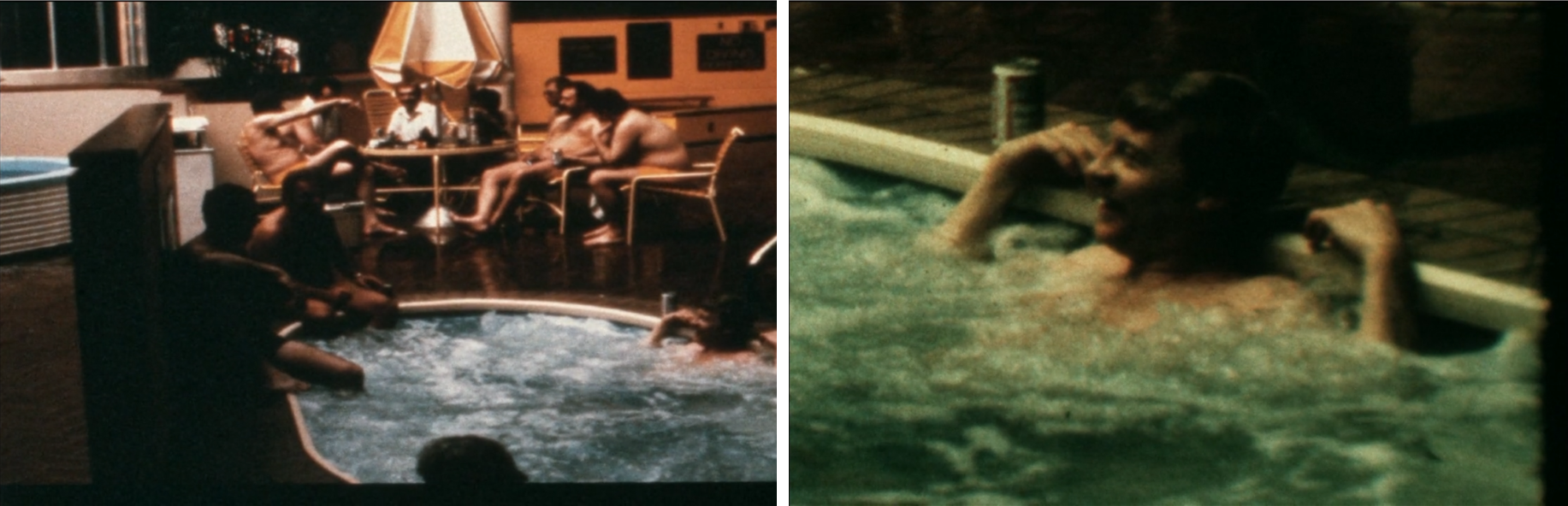

Chris Kennedy’s film also bears a sea name to talk about the media. Mysteriously enough, photographs that constitute The North Sea (Wave: Industrial Capitalism and the World) are separated by cards (“Page 1”, “Page 2”, “Page 3” and so on) letting you believe you are leafing through Kennedy’s family album above his shoulder, in 16mm. But sometimes, the numbers do not correspond to a picture change, making you suspect that you’re once more caught in one of the artist’s visual investigations (such as Watching the Detectives). The photographs seem taken in a holiday resort, some of the people are bathing in a pool, the others are sharing a drink under parasols. The camera gets closer and closer to the blurred faces and the water’s swirls while under the eye of the 16mm, the still images start to vibrate. Meanwhile, the yellowish colors and the dark exposure, associated with the ominous quote accompanying the film (“As Benjamin had predicted, nothing brings the promise of happiness encoded at the birth of a technological form to light as effectively as the fall into obsolescence of its final stages of development.” – Rosalind Krauss) leaves us with the same eerie feeling that one would develop in front of a vacation camp in ruins or a dried up sea.

Chris Kennedy, The North Sea, 16mm

Débordements n’a pas eu à traverser l’océan Atlantique pour assister à la seconde édition de Prismatic Ground et s’est contentée de regarder les films d’avant-garde et expérimentaux du festival depuis Paris, loin de New York, du Centre Maysles pour le Documentaire, du Musée de l’Image en Mouvement et de l’Anthology Film Archive. Qu’à cela ne tienne, le sentiment océanique des images en mouvement et des déferlantes (“vague” étant aussi la façon dont sont nommés les programmes), les mers et les fluides dansant sur nos écrans ont à eux seuls réussi à nous ôter au plancher des vaches.

C’est indéniablement une histoire étrange qui a d’abord retenu mon oreille lorsque j’ai commencé à me promener parmi les images mouvantes des différents programmes. Celle racontée par Frank Heath dans Last Will and Testament (Wave: Industrial Capitalism and the World) sur des plans du Canal de Suez, faisant à la fois le récit de l’arrière-plan historique et anthropologique de ce petit bras de mer et sa région, et du destin de cette entreprise pharaonique dans le capitalisme tardif. Le testament d’Heath connecte ces deux époques étranges : l’antique tradition mortuaire commandant d’enterrer les morts sous les routes pour protéger les voyageurs et l’hybris allégorique dans laquelle la globalisation contemporaine plonge ses racines.

Si vous traversez le Canal de Suez en direction de la Méditerranée jusqu’en mer Égée, vous n’aurez qu’à virer à tribord pour emprunter le détroit des Dardanelles, voguer sur la mer de Marmara avant d’atteindre le Bosphore et la Mer Noire. Là, se trouvent quelques unes des images qu’utilise Kamila Kuc dans What We Shared (Wave: The Memory of a Memory), un film dans lequel l’artiste emploie l’eau comme un écran de projection (ou un outil de montage ?) pour les archives de l’Abkhazie des années 1990 qu’elle a récolté. De l’effervescence de ces images et ces sons qu’elle livre à une IA, des formes et des idées nouvelles émergent, co-inventées par la mémoire humaine et artificielle.

“Après des mois d’obscurité totale” (puisqu’il s’agit-là du titre de la wave à laquelle appartient ce film) vous échouerez alors sur un nouveau rivage, quelque part en mer d’Irlande, recrachés par l’oeil d’un White Hole – saviez-vous qu’en physique, un trou blanc et l’exact opposé d’un trou noir, c’est-à-dire qu’aucune information ne peut y pénétrer, seulement en sortir ? Dans le film d’Eavan Aiken, nommé d’après cette sorte de singularité, cette caractéristique physique est traduite par un plan fixe lumineux sur une falaise battue par les embruns, sur laquelle défile un troupeau de vache apparemment sans fin, accompagné de musique jazz et d’un texte disposé entre les rochers.

Tandis que la lumière, les mots et la musique sont généreusement prodigués par le trou blanc d’Aiken, un autre film prend un pari sysiphéen : celui d’illuminer l’intérieur d’un trou noir. Arrivant à Guantanamo par la baie, le film de Katie Mathews et Jess Shane qui annonce sobrement son dispositif par son titre, Signal and Noise, alterne des images de cellules vides et les enregistrements d’ancien prisonniers (Wave: The Blessing of Liberty). Inspiré-es par le poète canadien Jordan Scott qui fit le choix d’enregistrer des sons plutôt que des images tandis qu’il empruntait le même parcours que les journalistes invités à montrer l’intérieur de la prison, les artistes utilisent le son des voix, des descriptions de sons comme outils de torture et les souvenirs du souffle de l’océan comme unique son porteur d’espérance à percer l’obscurité.

Le film de Chris Kennedy porte aussi un nom maritime pour parler de média. Mystérieusement, les photographies qui constituent The North Sea (Wave: Industrial Capitalism and the World) sont séparées par des cartons (“Page 1”, “Page 2”, “Page 3” etc.) laissant penser que nous feuilletons un album familial de Kennedy par dessus son épaule, en 16mm. Mais parfois, les numéros ne correspondent pas à un changement d’image, laissant suspecter que nous sommes une fois de plus pris-es dans l’une des enquêtes visuelles de l’artiste (comme c’était le cas dans Watching the Detectives). Les photographies ont l’air prises dans un village de vacances, certains personnages se baignent dans une piscine, les autres partagent un verre sous des parasols. La caméra s’approche de plus en plus des visages flous et des cataractes de l’eau, tandis que sous l’œil du 16mm, les images immobiles se mettent à vibrer. Pendant ce temps, les couleurs jaunâtres et l’exposition sombre, associées à la citation mélancolique accompagnant le film (“Comme Benjamin l’avait prédit, rien ne met en lumière la promesse de bonheur encodée à la naissance d’une forme technologique aussi efficacement que la chute dans l’obsolescence de ses derniers stades de développement.” – Rosalind Kraus) nous laissent avec le même sentiment sinistre que l’on développerait face à un camp de vacances en ruines ou une mer asséchée.

Website : http://www.prismaticground.com

2022 lineup : https://www.screenslate.com/events/prismatic-ground-2022