Tatiana Mazú González (V. O.)

“A dark and noisy and grainy film”

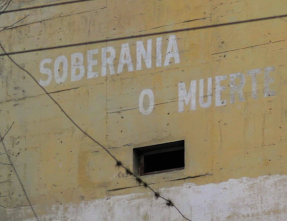

The 2024 edition of FIDMarseille sees the return of Argentine filmmaker Tatiana Mazú González — two years after the Marseille premiere of Río Turbio (Shady River, 2020) — with a new feature film. Todo documento de civilización (Every Document of Civilization, 2024) is an experimental and militant documentary about the disappearance and murder of Luciano Arruga (1992–2009) whose remains were only found in 2014. The story is told through the voice of the teenager’s mother, Mónica Alegre, and a haunting, atypical description of the event’s locations, filmed obsessively, at night, with glass filters and a noisy soundtrack. With Todo documento de civilización, Mazú González won, for the second time, the Prix Georges de Beauregard International. The following conversation — recorded after the film’s first screening at FIDMarseille — was an opportunity to unravel her filmmaking practice, consider some of the formal choices of Todo documento de civilización alongside her other films, and discover the polyphonic quality of her work, made within the framework of the collective Antes Muerto Cine.

Débordements: What came first, your interest in the neighbourhood as a place of study or the story of Luciano Arruga? Is it your neighbourhood?

Tatiana Mazú González: The neighbourhood is Lomas del Mirador, located in a district in the outskirts of Buenos Aires called La Matanza (matanza means slaughter in Spanish]). And it is where my maternal family has lived since 1960, more or less. My maternal family were Spanish immigrants from the post-war period, they were peasants. They arrived in that neighbourhood at a time when it was much less urbanised. The avenue, the Avenida General Paz, already existed because it was built at the end of the 1930s. But it was a much more rural space, as the scene with the archive materials somehow shows, where there is an idea of the passage from the countryside to the city and how at that time the state-building project in Argentina did not associate the countryside with barbarism and the city with European civilization. It is the neighbourhood where my mother grew up. My grandmother worked in her house because she is a dressmaker and my parents worked outside the house, so they left me with her most of the week during working hours. In a way, it’s not my home neighbourhood, but it’s the neighbourhood where I grew up for the most part. And it’s the neighbourhood where I’ve lived for the last ten years. I live three blocks away from the intersection of Avenida that we see in the film. In 2014, Luciano Arruga’s body was found buried unidentified in the largest municipal cemetery in Buenos Aires. That news came to me at a time when I was just planning to move to the house that had been my grandmother’s house. The people with whom my grandmother lived, her siblings, lived in a big family house. They died and my grandmother was left alone in a very big house. And my mom took her to live closer to her house and the house was empty and I moved in. And it coincided with that historic moment when, after five years, Luciano’s family and friends found his body. It strongly affected me as I started to pass by that space every day, that’s where this obsession comes from. For ten years I have been passing by that place every day. And I’ve looked at it in many ways and I’ve seen many things that I didn’t get to film, and I don’t know why. But it’s really an obsession, ten years of watching that space, going through that place on a daily basis.

D.: Todo documento de civilización has many things in common, aesthetically and politically, with Río Turbio, your previous film. At some point, you worked on both films at the same time, is that right?

T. M. G.: Yes, I was working on three films at the same time, actually. My three feature films so far, at one point they coexisted. And they contaminated each other in some ways. Particularly in relation to this one, whose beginnings are prior to the beginning of Río Turbio. When I started taking notes about Todo documento de civilización, and even when I started shooting a first batch of materials in 2017, Río Turbio didn’t even exist as an idea. I did have some questions in relation to my paternal family’s mining town, but it wasn’t crystallised into an idea for a film, I thought it was supposed to go somewhere else. But I had started writing and filming for Todo documento de civilización. And at that moment, when the film was more germinal, it was, I feel, a tougher film. A bit more forensic, so to speak, with more technical archival materials that addressed different ways of thinking about and representing that space, and at the same time hid what had really happened there, which was this forced disappearance of a teenager at the hands of the police. Perhaps it was a slightly more Farockian film. It was slowly transforming, right from the shooting. But then, some of those concerns and experiments I wanted to make in relation to the technical image, some time later, when Río Turbio emerged as a possible film, I also put them into practice there. Río Turbio is a film that has many more maps than Todo documento, and graphics related to meteorology and geology. Those technical issues somehow transferred from one film to the other. And for me that was positive, because it freed Todo documento de civilización from that, and over time I discovered that I wanted to explore other things with this film, which I already felt that I had somehow taken away my desire to explore in Río Turbio, for example: the question of approaching the technical image, the classic idea of documents. So, somehow, in this last film it remained latent in the second scene, where you see the archives of the construction and design of the Avenida General Paz. But later, the idea of the document in the film transformed: the document can be the garbage or the asphalt itself, or the sound we hear, even the female voice, or fantasy or imagination.

D.: Both films anchor political discourse in geographical description, but Todo documento de civilización gets really obsessive in the cinematographic description of that place, I’m thinking of the number of points of view we’re presented of the bridge area in the Avenida.

T. M. G.: When I was a teenager, around sixteen years old, I started to think about what I wanted to do with my life. I had two paths, one was to be a geographer and the other was to be a filmmaker. Well, it was either a geographer or a biologist: my hesitation was between one of those sciences or to go for filmmaking. I ended up with filmmaking because I felt that academic life was not for me. I’m an agent of chaos, with my processes, my ways of working, I can’t use an agenda, I’m a mess. And I felt that cinema was going to allow me space to breathe when it came to organising my work and my interests a little more freely. I abandoned the path of science, but it is something that has always been in my mind. And the question of what human traces are carried in space, or of the social transformation of the space, is a question that, evidently, always interested me, and that becomes more evident with each film I make. I am fascinated by empty spaces, I am fascinated by rocks. I have a collection of rocks in my living room. I love to observe the idea of the trace, of what persists and, somehow, as something almost unknown, a hieroglyphic which we have to dig up a little, can still continue to ask ourselves questions from the past to our present and to our future.

D.: The soundtrack is balanced between experimental sound design — with various layers of noise — and a recorded voice reminiscent of investigative journalism. Can you tell me more about your approach to sound in film?

T. M. G.: The work with which I pay for rent and food and that sort of thing has more to do with graphic design and art direction, and costumes in fiction films. I’ve illustrated a lot of children’s books, for example. And the orientation I had in film school was photography. I’ve had quite a lot more training in these fields than in sound. The question of sound arrived when I made my first film, Caperucita Roja (Little Red Riding Hood, 2019) with my maternal grandmother, with her teaching me how to sew and talking about work and migration. That’s when I realised I have no training in sound. I never took a music class, I don’t play an instrument, I had a lousy education in sound. Wanting to learn more about that, I began a collaboration with Julián Galay. Julián has been my friend since I was seventeen and he doesn’t have a background in film, he is someone who has had a musical education since he was very young. We started teaching each other the practices we knew best. That’s how sound experimentation ended up being fundamental for me when a film’s conception. Julián is now making his first film as a director, for which I’m the cinematographer. It’s been almost ten years of teaching each other, a sound-image collaboration that goes along with our friendship. In Argentina it is very common that sound training is bad in cinema: they teach you to make a very mimetic sound, very prefabricated, and screen-centric. In fact, in Argentina, the one who brought a lot to the table regarding sound education was Lucrecia Martel, who at one point became obsessed with these issues. And after her, people started to pay attention to this matter. But that situation generated more questions than problems for me, as it opened a field of research and I began to feel that in the image-sound dichotomy, sound was somehow oppressed by a mostly visual culture, where although the sound is constantly influencing us all the time, we pretend it isn’t. And for me there is something of that, of the marginal, that always interests me as an alternative path. And I started to relate a lot to sound also from the perspective of feminism. Many of the great pioneers of experimental music are women, they did something that nobody cared about and it’s precisely their condition as women that allowed them to dedicate themselves to something non-productive. The same happens with experimental cinema in many cases. There is something there that attracts me a lot, sound art and sound experimentation, even in terms of gender, which in the end also ends up being closely related to the question of listening, with listening already in political terms more linked to questions of empathy. In fact, many metaphors in the works of the feminist movement have to do with sound, with raising one’s voice, for example. So, I feel that there is a whole path between the experimental and the political. That was put together for me, as one little step led to the other. And I like to find ways for that to coexist without stepping on each other. What I like about this film is that I feel there is a balance between those moments in which the sound allows us to imagine another planet or the depths of the earth or the violence inscribed on the asphalt, and moments where the only thing we need is the simplicity of that voice.

D.: How did you approach the recording work with Luciano’s mother? Also in relation to your attention to space.

T. M. G.: I am a rather shy person. People think I am not, but it is very difficult for me to approach people I don’t know. And I feel that I also found, from my concerns and my intuitions and interests, ways of approaching people through film, which were less invasive to others and to myself. So, for example, I feel very comfortable observing spaces and observing the evolution of spaces and looking for the traces of the human and the political there. I also feel very comfortable chatting without recording images, for example. I feel that I am less invasive towards the other person, that we are more sincere when we listen to each other, less aware of that tension that the lens generates sometimes. The world is full of obstructions and oppressions and restrictions and I try, as impossible as it is to be isolated from everything that happens, to make formal decisions, but also tying the formal to what has to do with the craft, with practice, with sharing, with the material that each formal decision implies, that these are situations where I feel comfortable and where I feel that other people can also feel comfortable. This is something that I’ve realised over time: if the world is horrible, at least I can try to build, within the exercise of my films, a zone as temporarily autonomous as possible, where we try to set the rules ourselves. I love talking to people and understanding their life stories and reading them in a political way. I don’t like to invade them with a camera and at the same time I’m obsessed with spaces and traces as a form of knowledge. So, I think there is something there that was woven between one film and the other.

D.: Was the recording planned as an interview or as an informal conversation?

T. M. G.: In my university days, I used to be in several collectives linked to left-wing counter-information, where I learned many important things for my life and politics, but where I also struggled with the many ways of conversing with people. The idea of the questions that you write before meeting someone and asking them, which really means “I need this from you”. To me it was something that did not make sense and there was no possibility of knowing what I was getting from the other person, but I was going to look for what I thought was useful for my discourse. There was something about that which I didn’t like and I began to avoid. My student film El estado de las cosas (The State of Things, co-directed with Joaquín Maito, 2012) had conversations in it, but there were no prepared questions. It was a film about an antiques auction house, but we didn’t want to talk about that. We were interested in exploring what relationship these people had with the objects, with the material, the use value, the exchange value, the affective value. There were some themes, some concepts, but it was ridiculous to ask people about them. So, they were very free conversations and they taught me that one could easily resonate with another person in relation to the topics that interested them, without the need to force the person to talk about it, but finding points of contact between interests, which after all is what a conversation is. This is something that I later continued in my three single-authored films: if I’m going to record a conversation with someone, I’ll never go with anything in mind, other than the desire to have a conversation with that person. And I generally don’t ask questions. I usually state my intentions: I feel like sitting down and chatting with you, because of this, this and this, I’m doing something in relation to this. And I try to give them a space in which to talk. And people talk a lot.

D.: This statement of intent is present in Todo documento de civilización. You left this part in the soundtrack.

T. M. G.: Yes, I left it. I had been wanting to leave it in Río Turbio. That’s where the films are asking each other questions. I wanted to leave more traces, or some trace, of that instance of communication in Río Turbio, because they were also very intimate conversations. I mean, I would never record a conversation with that degree of intimacy with a film crew, for example. I recorded this one alone with her and a very simple recorder. And the ones from Río Turbio as well. I was there with Florencia Azorín — who is the producer of the film and a great friend and collaborator in a very broad sense — alone, eating cookies, something very far from the idea of a normative shoot. And for me that’s important, I feel that sometimes cinema is very invasive. And particularly, in the case of Mónica, Luciano’s mother, she is a person who has been talking to the mass media for many years. And obviously, many of the things that the film says never appeared in those interviews, precisely because of what we were talking about, because perhaps sometimes there is a great inability to listen, in a deep and active sense. She is a wonderful storyteller, she can put a lot of nuances in a single sentence, of tone, of intensity, and that seemed amazing to me when I thought it was going to be the first of dozens of conversations until she appeared and I sat down for five hours to have lunch with her and I said to myself, “What more can I ask from someone than this that she just gave me?”

D.: I would like you to talk about the use of noise in your film. I’m not talking about the noise in the soundtrack, but the visual noise. And also about the way you filtered the images with glass.

T. M. G.: In Río Turbio, the digital image is generally a very clean 4K, but there is also analogue film present. I’ve worked on the idea of opacity and darkness, and those elements do appear in the project. Working on Río Turbio, the image that came to my mind all the time was what is called suspension dust, which is this coal dust that flies down the mine, shiny and black. It was one of the images that guided me when making formal decisions. Other than that, the digital material in that film is clean. Regarding Todo documento de civilización, one of the first things I wrote down is a sentence that goes like this: It’s a dark and noisy and grainy film. Among the first intuitions for this film here was an idea of texture and colour. For me it was a night film because Luciano’s disappearance happened at night, because it’s at night that police have control of the street. There’s also a sweeter reason, which is that I imagined a woman telling a story to her son before going to sleep, during a cold winter night in Buenos Aires. I wanted the film to be at the same time a document of civilization and a document of barbarism, thinking of reality as something that has layers, where sharpness doesn’t really exist. And what is shown as sharp is actually opaque. There was a conceptual and political relation to the idea of the construction of truth or the construction of reality and what a document is and how a place of passage is in reality a place of death. I was haunted by the feeling that gave me the act of passing by that place every day. So I started to think about it visually. And there began a conversation with Francisco Bouzas, the cinematographer. I told him I was fed up with sharpness in cinema, that I was increasingly tired of 4K, where you can see everything, where seeing more is supposedly seeing better. And so we started first, in 2017, filming everything through glass with vaseline, following the idea of layers that are hidden. Years later, once Río Turbio premiered, I started to assemble Todo documento de civilización and started working with what I had, which were these images shot through crystals plus the conversations with Mónica. And I started to feel that when she was talking, I couldn’t see the city, I needed to see something that looked like a mental image. And my mental images are fuzzy and grainy and they don’t have definite edges and they look a little bit more like a shadow in some dark place in my head. Thinking about how to shoot these mental images, I thought of the analogue image, which is more organic, it admits error, other softnesses and other roughnesses that the digital image, at first glance, seems unable to give us. But the material conditions we have had in Argentina in the last fifteen years makes it economically impossible to use film for a feature. But then again, something that appeared as an impediment, actually ended up becoming an opportunity or a challenge. How to solve this dilemma without using analogue? So we used the 4K cameras in a way they shouldn’t be used, forcing them, pushing their ISO sensitivity to the limit, like 450,000 ISO. We kept changing camera models as well, not everything was done with the same camera. It was interesting to see that with video it was also possible to go to those places. We started to make the joke that it was the film of the poor.

D.: The title of the film is a quote from Walter Benjamin: “There is no document of civilization which is not at the same time a document of barbarism.” But maybe there’s more traces of Benjamin in your film, if one thinks about his method of assembling fragments in Das Passagen-Werk…

T. M. G.: I read the Theses on the Philosophy of History — which is the text that I quote in the title — when I was a student. At that moment it resonated with me as a text on cinema and on montage, precisely. When he conceives history as something that jumps backwards and forwards, and not in a unidirectional way. And he talks a lot about this idea of the leap, which to me is very much like the idea of the cut. Or he talks about how to evoke the past. Or again when he says that remembering is like a flash of lightning in an instant of danger. It seems to me that they talk about, perhaps unintentionally, audiovisual narrative and montage operations, they’re metaphors of cinematographic montage.

D..: Towards the end of the film there is a moment where the narration of what happened to Luciano comes to an end: we already know what happened, more or less. And in that moment, for the first time, we see images of Luciano’s mother. I would like to know why.

T. M. G.: I remember when I screened a work-in-progress version of the film a programmer said to me: “Why do you show her at the end? In Río Turbio you didn’t show the protagonists it and it turned out well.” There are a lot of things for which I have rational answers and I defend having them and I like to have them. And there are other things for which I may not have the perfect answer. And I think this is one of them. I feel like it’s more intuition or whim. I don’t know if I always want it to work out well or if I want to try something else, and see what happens. Also, in Río Turbio there was something that interested me a lot, which was creation as a sort of collective voice. There are twelve women who speak in that film, and in Todo documento there is clearly one character. Beyond the fact that she is giving an account of a collective struggle, she is talking about herself as well. The arc of her voice, in this case, besides telling the story, as you say, tells her story. I don’t think it’s a film about the case of Luciano’s forced disappearance. I think it is more a film about the space where it happened and about her story and how she transformed from that woman — a single mother, who was not politically involved and who told her son to look down when the police chased him — to what she is today, which you can see at the end of the film. So, for me there’s a curve there, and it forms an arc. After we heard it, maybe then it’s okay to see it. I am very fond of that shot where she appears screaming, because it was filmed during a quarantine in a very small demonstration in downtown Buenos Aires, where there were very few people.

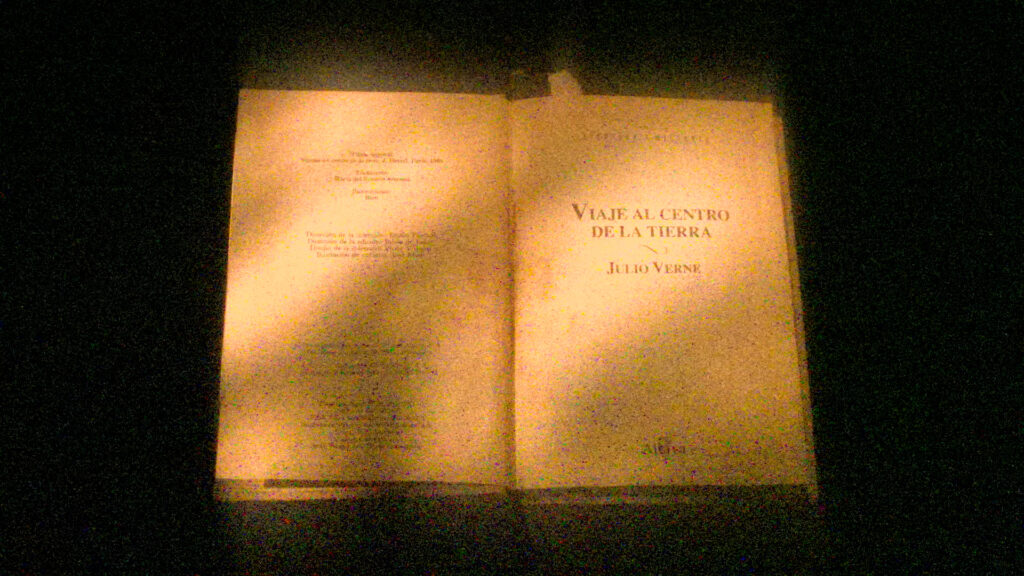

D.: With the appearance of Mónica the film turns towards the future, towards utopia, in a positive sense. The film evolves. We see Mónica, then some illustrations of Jules Verne’s books depicting a rocket, and then images of an uprising. And we hear anti-fascist songs.

T. M. G.: Yes, there is something, as you say, of a becoming that for me was not only narrative, it’s not only a question of editing, it was a further step of the creative process of the film, of uncovering layers. The film, as I told you before, was initially a more forensic project. In fact, when we started filming, this more observational attitude went through the distortion given by the glass. But then, when a year later I recorded Mónica’svoice, it became something else. And when two years later I started editing, it became something else again. When I recorded the conversation and she shared with me Luciano’s interest in Verne’s novels, it opened a new current in the film that had not existed during the previous three years. So, in a way, the structure of the film reflects the process that I went through myself, of discovering new edges and layers. It also opened up new political questions for me, and also the presence of the future, about the possibilities of a child or an adolescent in the poor neighbourhoods of Buenos Aires. Verne’s biography is full of interesting topics, from anarchism to technology. I found it interesting to think about which of those issues would resonate with a teenager in my neighbourhood and which ones resonate with me today and to establish those links that, in the end, do not seem so far away from the Benjaminian question in relation to progress. Because another thing that Benjamin brings to Marxism, has to do precisely with shaking this idea of progress that is present in the most orthodox Marxisms of the beginning of the century. The film ends with images of a demonstration that takes place every year in our neighbourhood, which always ends with a fire. They build these cardboard police cars that they set on fire, and they dance around the fire, and that is the annual ritual, which also has something tribal about it, which brings us back to the illuminist dichotomy of civilization and barbarism.

D.: One of the last things we hear in the film, in the demonstration scene, is an act of curiosity, and an act of sharing: a kid asks “What is this?” and the sound engineer gives him his headphones. There’s a cut, and instead of hearing the fire that we see on screen, we hear the sea.

T. M. G.: It’s waves. Something I’ve been asking myself lately has to do with imagination. I feel that a great part of the historical defeat that we are experiencing, and that is now allowing this new wave of a global ultra-right-wing, has to do with the fact that we have lost the ability to imagine that this other world, however diffuse, in the background and on the horizon, it may be, is a real possibility. It is difficult to find someone who tells you, “Yes, I believe that at some point this is going to be better. I imagine a world like that.” A century ago it was much easier to find someone to say, “We are going to have revolution and there will be socialism and we will all be equal.” I think there is something about imagining another possibility for the world that today is very truncated. Making this film has a lot to do with how to recover the ways of imagining, and how fantasy or imagination can be a political tool that we need as adults. This way of ending the film arrived very late: until mid-April, once the fire scene was over, it would go back to the crossroad and there would be daylight. But the image continued to blur and life continued to go on as if nothing was happening. And we had long conversations with my colleagues in the collective of which I am part of, Antes Muerto Cine: “What question do we want the spectators to leave the theatre with in relation to the present, in relation to reality?” Trying alternatives that were not closed and false ambitions was a real group exercise. We found the conversation with the child while reviewing the materials. In the first attempt, the child listened to the fire. But Julián told us that what we had to listen to had to represent imagination. Curiosity triumphs because the child listens to the sea where there is fire. For me it was a way of not losing optimism altogether, embracing that possibility of the future, through imagination.