Return to the scene of the crime

On Wang Bing's Traces (2014)

For the past twenty years or so, independent filmmaker Wang Bing has been working around two main themes. On the one hand, the documentaries Tie Xi Qu: West of the Tracks (2003), Crude Oil (2008), Coal Money (2009), Man With No Name (2009), Three Sisters (2012), ‘Til Madness Do Us Part (2013), Father and Sons (2014), Ta’ang (2016), Bitter Money (2016) and Mrs. Fang (2017) are consecrated to the careful observation of common people’s everyday routines, providing a compelling, Direct-Cinema-like look at how the other half lives and dies in the lower depths of present-day China. On the other hand, the documentaries Fengming, a Chinese Memoir (2007) and Dead Souls (2018), and the fiction films Brutality Factory (2007) and The Ditch (2010), constitute a historical investigation into how the Communist Party of China dealt with ideological dissent in the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s.[11][11] Shot over the course of seven days in December 2005, Fengming, a Chinese Memoir exists in three different cuts, each one with a different runtime and release date. Here I will discuss the three-hour theatrical version that premiered at Cannes Film Festival in 2007. For information about the other two versions, conceived for art gallery spaces, see Wang Bing, Alors, la Chine. Entretien avec Emmanuel Burdeau & Eugenio Renzi, Paris: Les Praires Ordinaires, 2014, pp. 100-113.

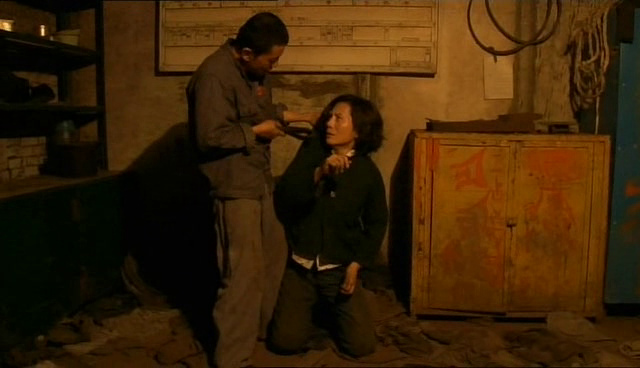

Set in 1967, during the early years of the Cultural Revolution for the definitive eradication of “reactionary bourgeois” from Chinese society, the short film Brutality Factory stages the political police torturing a woman accused of being a “counterrevolutionary”. According to the torturers – whose mix of Maoist fanaticism, ruthlessness and clerical ennui would make anyone’s flesh creep – her husband has already proven his guilt, because he “committed suicide by smashing his skull into a brick wall”. However, the authorities want the woman to formally accuse him of “rightist conspiracy” in order to close the inquiry. Otherwise, she will be considered “an enemy of the People” and treated accordingly.

Literary adaptation The Ditch and interview-driven documentaries Fengming, a Chinese Memoir and Dead Souls tackle the subject of the Anti-Rightist Movement that immediately followed Mao’s 1956 Hundred Flowers Campaign for freedom of expression. Based on Xianhui Yang’s 2003 short story collection Gaobie Jiabiangou and on Wang Bing’s own research work, The Ditch reenacts the captivity memories of real-life people who survived the Jiabiangou and Mingshui camps, in the Gobi desert, where alleged rightists from the Gansu province were sent in the late 1950s to be re-educated through labor. Of the almost 3500 political prisoners interned in Jiabiangou and Mingshui between 1959 and 1961, around only 400 survived, some of whom relate their ordeal in Dead Souls. Among those who didn’t make it, deliberately starved to death by the Gansu local government, was Wang Jingchao, husband to He Fengming, the woman who recounts to Wang Bing the story of her life from 1949 onwards in Fengming, a Chinese Memoir. Not only was He Fengming accused of being a “rightist element” and forced into a labor camp during the Great Leap Forward, but she again suffered public humiliation, political persecution and confinement during the Cultural Revolution, until her final “political rehabilitation” in December 1978. Her deceased husband was politically rehabilitated in 1979, together with 99,9 percent of the over half-million people officially put on trial during the Anti-Rightist Movement. What happened in Jiabiangou and Mingshui remained a state secret of sorts until the 1990s, when a series of books on the subject (including He Fengming’s own autobiography) began to circulate semi-clandestinely in mainland China, opening little cracks in the state-sponsored wall of silence that, as explicitly stated in Dead Souls, lasts to this very day.[22][22] Not coincidentally the working title of Dead Souls was Past in the Present. See Wang Bing, “Past in the Present. Director’s Statement”, in Sabzian collective (eds), Wang Bing: Filming a Land in Flux, Brussels: Courtisane Festival, pp. 60-62.

The 30-minute Traces (2014) is the one and only movie Wang Bing has shot on film so far, and belongs to the above family of historical exposé works. It was shot in July 2005, during the pre-production of The Ditch, as Wang Bing was scouting for locations in the Gansu province, in a desert area where the Jiabiangou and Mingshui labor camps stood from 1957 to 1961. In addition to his own MiniDV camera, the filmmaker brought along some black-and-white 35mm film stock, a gift from fellow-director Yang Fudong that Wang Bing decided to use to film “a landscape about to disappear” [un paysage voué à disparaître].[33][33] Wang Bing, Alors, la Chine, opus cité, p. 33. In fact, the desert wind constantly changes the look and shape of the territory, and – most importantly – civilization is conquering the Gobi wilderness little by little, as demonstrated by a shot showing trucks speeding across the desert on an asphalt road. However, for Wang Bing, something more important than the preservation of natural beauty is at stake here.

From its very title, Traces asks: what remains of Jiabiangou and Mingshui today? Apparently, not much. As part of a cover-up campaign launched by the Gansu local government in agreement with the Central Committee of the Party, the two labor camps were evacuated in early 1961 and definitively closed down later that year, letting the wind, the sun, the snow and the wild animals take care of debris and dead bodies, and erase all evidence of wrong doing. Just to be on the safe side, the prisoners who managed to survive famine by ingesting anything they could find (wild grass, seeds, tree barks, dirt, worms, rats, human flesh, feces and vomit) were scattered at the four corners of the province, mostly in remote country villages, and so were the cadres of the camps. Finally, the word “starvation” was banned from the death certificates to be issued for the official records, and substituted with “natural causes”. According to the Party, the “Jiabiangou incident” was closed and not to be mentioned ever again: the “enemy within” had to be dealt with and a “public service” was conducted. This is the very same euphemistic, Orwellian language used by the torturers in the short film Brutality Factory, which ends by showing the dismantling, sometime in the late 1990s, of the industrial complex where the Cultural Revolution’s “struggle sessions” took place – a clear objective correlative to the progressive erosion of Chinese historical memory under the pressures of the powers that be.

Yet, covering up murder is not as easy as killing people. As Traces begins with a series of hand-held shots showing human bones emerging from the Gobi desert’s arid terrain, I was instantly reminded of what a former member of an extermination-camp sonderkommando tells Claude Lanzmann in Shoah (1985): certain types of bones always resisted cremation, and had to be ground into powder manually after the corpses were burned. Similarly, the bones of those who were killed in Jiabiangou and Mingshui during the Anti-Rightist Movement resisted atmospheric agents and wild animals up until 2005, when Wang Bing filmed them, unmistakable evidence that something did happen in Gansu, in “the land between the ditches” [jiabiangou]. What happened exactly, the bones can’t say, unfortunately. But at least these long-lasting mineral traces can incite curious and obstinate people like Wang Bing to investigate the questions of why a desert plain is scattered with hundreds of human bodies decomposing under a thin layer of dirt and rocks. Who were these people ? When did they die, and how ?

As a matter of fact, with Traces, Wang Bing finds an ideal brother in Chilean documentarist Patricio Guzmán, director of Nostalgia for the Light (2010) and The Pearl Button (2015). Just as Guzmán rummages the Atacama desert and the Pacific Ocean floor looking for the remains of the left-wing dissidents that disappeared during Augusto Pinochet’s fascist dictatorship, the Chinese filmmaker searches the Gobi desert for evidence of a covered-up political massacre. Unlike Guzmán, however, Wang Bing does not address viewers through a voice-over commentary, preferring instead to let the images speak for themselves, while the sound of his footsteps, the wind and the noise of a running film projector take the place of a soundtrack. The last few minutes of Traces are the best examples of this attitude, and are profoundly touching. After wandering through innumerable, improvised burial mounds with rare, handwritten gravestones made unreadable by decades of wind erosion and snowfall, the camera enters a series of natural caves that, as told in Fengming and Dead Souls and as shown in The Ditch, were used by the starving prisoners for shelter at night. When the camera exposure is adjusted to the semi-darkness in the caves, Wang Bing pans around and frames an ideogram poorly carved into the stone wall and reading “Freedom”: it’s the voice of thousands of oppressed people screaming at the top of their lungs.

By the time Wang Bing decided to make Traces in 2014, the film footage he shot in 2005 had become scratched and somewhat decayed. But, as a matter of fact, these days the Jiabiangou and Mingshui remnants are in much worse shape than the beat-up 35mm negative. According to Wang Bing, the crime scene depicted in Traces has become a building site since the early 2000s, and has been developed to the point that, by the start of the shoot of The Ditch in 2008, the original location of the labor camps was “full of houses” [encombré d’habitations].[44][44] Ivi, p. 118. Wang Bing therefore decided to reconstruct the labor camps 200 kilometers further into the desert for the shooting of The Ditch, also in order to avoid interferences by the local authorities. As the Gobi wilderness was colonized and turned into a city, what happened to the bones of the Jiabiangou and Mingshui victims? Have they been removed? Have they been ground to powder and dispersed? Have they been buried under an impenetrable layer of asphalt and concrete? Have the caves been blown up to make room for a highway, a railway, an apartment building?

Most probably, the 2005 footage incorporated into Traces is all that remains of Jiabiangou and Mingshui today, a sequence of images that will survive for a while on film or as digital data, before disappearing when the storage medium fails or becomes obsolete. As with anything else, cinema is not eternal. In the hands of filmmakers like Wang Bing, though, cinema can become an instrument to extend human memory and make it less fragile, so that oblivion can be held at bay for a little while longer.[55][55] As a proof of the cruciality of Wang Bing’s work, it should be noted that Traces slightly predates Ai Weiwei’s 2015 artwork Remains, which consists of life-size porcelain replicas of some human bones dug out from an undisclosed place where a labor camp for rightists stood in the late 1950s and early 1960s.