Selçuk Artut (V. O.)

Soyutlamalar (Abstraction)

On Sunday 11th 2025, Istanbul Experimental and Salt Beyoglu paid tribute to Teoman Madra. This artist is one of the first to explore video art in Turkey, at the turn of the 1980s, before devoting himself to digital art. On this occasion, Selçuk Artut (visual artist and theoretician specialized in media art) gave an unprecedented insight on Teoman Madra’s work, projecting rare images from the artist’s private archives. We invited him to unlock the “black box” and give us his source code to help us approach Teoman Madra’s experiments. Beyond the portrait of an artist, Artut provides a cross-cultural archaeology of Turkish media art.

Débordements : How did you become interested in Teoman Madra’s work as a researcher and practitioner?

Selçuk Artut : This work concerns me directly because it addresses important issues for my practice. I have to say I don’t have a classic artistic training. I grew up with the ambition to become a scientist and I studied mathematics. But while studying mathematics, I was still in other areas, including music. Music was a big drive for me. And then, in 1998, I met with these guys, we formed a band called Replikas, and then we started playing. We were not a traditional rock band, but instead very experimental, sound-based, noise-based…

I started making sound installations with the use of computers and technology and codes and sensors and similar things back in the 2005. I was using various software and creating my own interfaces. Which is another manner of achieving digital luthierism, to make my own digital instruments. Then, I realized I wanted to pursue a career in academics and have a PhD. I applied to the European Graduate School, and started working with Professor Siegfried Zielinski. I became interested in the preservation of media artworks, an issue that I felt galleries, exhibition spaces and cultural institutions weren’t paying enough attention to.

I began working on a book, approaching institutions such as ZKM (Zentrum für Kunst und Media in Karlsruhe, which works to preserve works of media art), Tate Modern and Rhizome. I became my own case study, as I too faced the problem of how to preserve my works. I was reading an article written by Ekmel Ertan (Turkish artist and scholar who specialized in art and technology interplays). He was writing a media art history of the Turkish Artists, and I was included. I wanted to know who it was before me, since media art didn’t begin in the 2000s.

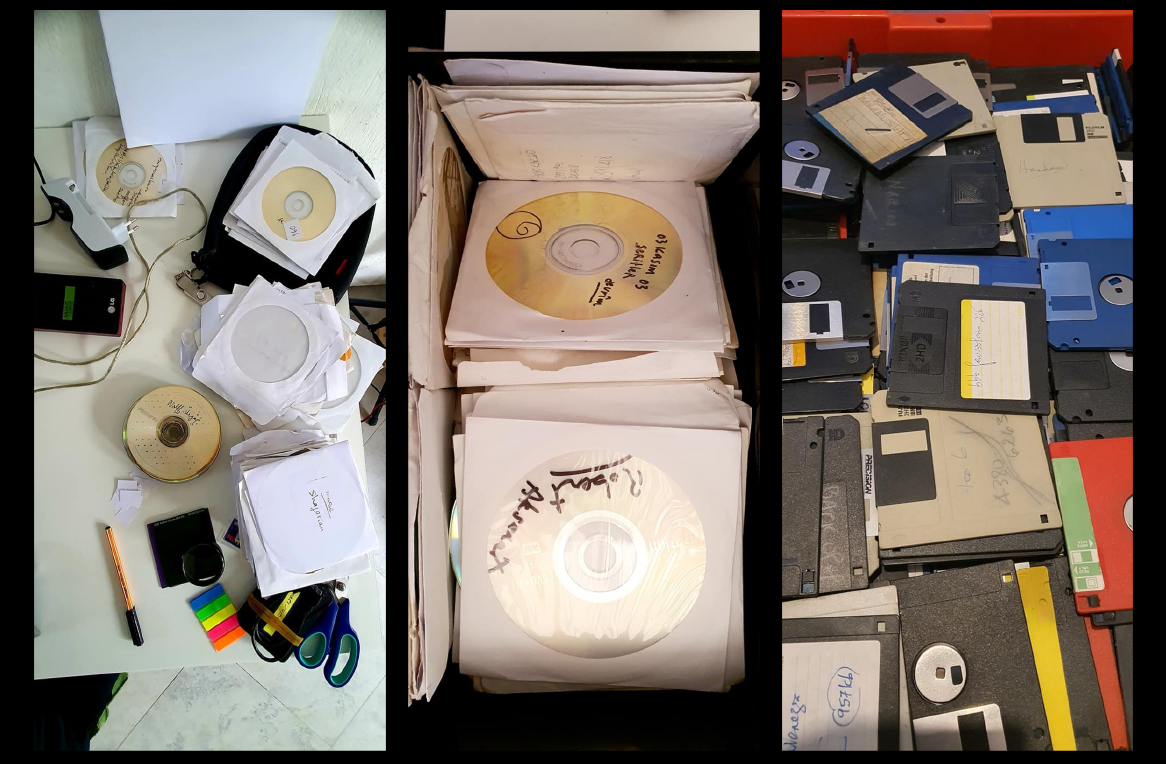

There I saw Teoman Madra’s name. I knew his wife, Beral Madra, who’s a very acknowledged curator. She invited me to Ayvalık, which is a five-hour drive from Istanbul, a sea-side place. And I went there, and I realized there was a huge heritage, dusted shelves full of VHS tapes, CDs, hard drives, prints and everything, which were about to decay. Teoman Madra was in a mood of dementia. I wasn’t able to communicate with him, and I felt some urgency: I had to digitize these things, because physically they were eroding. I took responsibility to put everything in my car, and drive back to my home and start digitizing them. That was the period when I started to get more exposure into his work.

I became interested in his works from the ’60s and ’70s, which are more into experimental photography, using light sources in front of a camera and long exposures, so you can create patterns. But these patterns were not any kind of patterns, he was using a lot of music in it. He was listening to a lot of avantguard composers, like Ornett Coleman, John Cage, and Turkish composers, like Bülent Arel, İlhan Mimaroğlu, İlhan Usmanbaş. He was into all sorts of experimental composers. And he was creating these light patterns, but you could easily realize they had some harmony, there was some gestural meaning into it. I said: that’s quite a nice match, because music was his drive too! I felt like I should protect these things first, and then create such an exposure that Teoman Madra would be known to more people. I always describe it as a brick missing in the history of the Turkish media arts.

D.: Let’s talk about this shared passion for music. Reference to music is quite common in video art and what you call “media art”, which includes more generally the artistic uses of new media. The first video synthesizers were based on music synthesizers. Do you think there’s something specific to Teoman Madra’s work? You talked about his work with torch lamp and long exposures, which suggests an almost choreographic approach to photography.

S. A. : Yes indeed. In some occasions in the archives, I found descriptions of him dancing when he was doing these things, to those music I mentioned. But later, in the ’80s, it’s becoming more evident, because he is doing temporal artworks, in which he directly includes music. In the mid-80s or 90s, I think, he continued his exploration of “generative art”, I would say (it’s like an umbrella term), from a multimedia perspective, in which he combined sounds and images together. He always mentions “synethesia” as a main ingredient of his works.

The main difference, if you were to compare my work and his, is that he wasn’t a musician. He was a really good listener, using most of the time very experimental stuff, and some kind of music which was very difficult to describe as a “musical”. At that time, he was working with musicians very close. In the ’80s, for instance, he was working with a musician called Okay Temiz, a Turkish experimental musician again who was into percussions and drum music, and they were doing jazz concerts together. When the band was playing, he was presenting his videos. He created generative works, even though his tools were not meant to be used that way. He used for instance Deluxe Paint, which was a program built for graphic designers, and had nothing to do with time-based media, but he was still experimenting with it. He used capture devices, totally unknown to most of the people, created feedback loops, presenting the camera to the screen and creating feedback loops, so that the still images become time-based, evolutive images. The latency in the loop generated the artwork.

So at that particular time, rather than dancing, he was using a mouse to accompany live music. But his works weren’t supposed to be visual equivalents of the rhythmic pattern, it was about creating patterns and generative visuals. In the ’90s, he buys a Mac and a PC, and in 2006, he gets an iPad. He was still doing things on the iPad, while listening to music: he was an active listener.

D.: Talking about music, you highlighted the technical evolution of Teoman Madra’s tools, through technical obsolescence. How did Madra approach these new tools?

S. A. : Let’s rewind a little, at the time when he returns in Turkey after studying agriculture in the US. During his obligatory military service, he meets with an officer, and then buys a photocamera from him, Voigtländer’s Bessamatic (it’s a German brand). That camera enabled him to make long exposures, and it was I think his first technological tool to be used artistically. Then, he started building his own lenses and everything. Unfortunately, we don’t have much material left to talk about this.

In 1985, a Turkish company, who was into selling computers over here, gave him an Amiga 1000 computer. There he started using software and buying capture devices, and using cameras and all these sorts of things. He was a maker, so he could buy some tool but it was never enough for him, he needed to build extra stuff, to modify them. And, as I said, in the ’90s, he built some personal computers. Finally, from 2006 onwards, until I think 2015 (he was active until then), he was using iPads, combining his photolight pieces with digital artworks, making multimedia collages as well. This is his technological evolution.

But from the “output” side of things, he was using analog medium before moving to Betamax tapes, VHS tapes, and then PCs arrived. He started using CDs, floppies, and later on hard drives. Then he was into—something that I’ve forgotten—, into Internet art. In 2000 (I don’t know, I can’t be very precise about the date), he built a website called NewMediaKitchen, in which he was also presenting his artworks. These changes may seem quick, but the shift from VHS to computers actually took quite a long time.

Something I also commonly share with him is his critical approach to technology. He focused on using innovations for experimental results, not to comply with their usual use. So referring back to Deluxe Paint: it is used by graphical designers, but he uses it as if it was an “after effects”, like a motion design program. He was able to invent his own path by experimenting. The “modernist” approach to technology will say whatever comes out is a progress, and should be accepted as such. On the contrary, I think Teoman and I have a more “postmodernist” approach, which traces where technological innovations come from and then make experiments with it and make sure that it will be good for us.

D.: What do you think of a materialist approach? Speaking only of hardware, the tools Teoman Madra used, like perhaps some of your own, are the product of American tech capitalism, based on the exploitation of raw materials in the Global South. Shouldn’t the industrial origin of these tools also be questioned?

S. A. : It’s a good point, but that’s not what I was thinking about. I mobilized the idea of “origin”, in the sense you can ask: where do algorithms come from? As we know, Al-Kwârizmî was a Persian mathematician. So, yes, maybe, from a materialist point of view, I think your perspective is right: our access to technology is determined by the material conditions of their production. But I think today, with the democratization of the Internet, we can break these barriers to some extent.

During the Islamic art enlightenment period—a period I’m interested in for my own work—, the idea of intellectual property didn’t make any sense. Works from that period are all anonymous. Why would I hide something that I know from the others just to get a better benefit? I’m for sharing knowledge and tools, and, if there was a need to prove it, I published a book two years ago in which I’m giving all the codes to readers so that they can reproduce my artworks. I’m more into the open-source.

Talking about cultural imperialist point of view, I think the “Fine Arts” notion was created in the Western culture. I don’t mean to oppose East and West, but it’s true that at some point in the East, art has been anonymous and there was no separation between the artist and the person from the crowd. The art person can also paint a wall so it’s about doing and making. But then, with the enlightenment, there was this idea that art should be owned, like a property.

D.: Did the history of Islamic Enlightenment matter to Teoman Madra and other Turkish artists of his generation, such as the members of the NOMAD group (a group initiated by Başak Şenova, Emre Erkal and Erhan Muratoğlu in 2002, dedicated to digital experimentation)? It seems Madra was a relatively solitary artist, despite his many collaborations; he was never part of a group or workshop.

S. A. : Let’s say his relationship with Beral Madra, who was a very acknowledged curator, provided him with some network and some influence. He was friends with John Cage, had conversations with Nam June Paik, he used to go out with Fluxus artists. He even recorded some Fluxus performances. From the ’90s onwards, Teoman Madra gets a video camera and starts documenting almost systematically different events of his life. That’s another part of his archives I haven’t mentioned yet: the documentary part.

Going back to your question, he collaborated indeed with musicians and artists, including NOMAD. Theses underground artists knew him because he was also going into their shows, meeting with them, and he was invited to show his works when they organized something. But he was friends with İlhan Usmanbaş, who also lived in Ayvalik. Usmanbaş is a Turkish composer, more into the academic side of things. He had links with İlhan Mimaroğlu, an electronic composer. But he’s never been a part of a particular family of artists, he wanted to keep his independence, as an individual artist. So I would have difficulty finding a group such as, as you mentioned, NOMAD. He never wanted to be part of it, but rather to be around and exhibit and present his works I think.

D.: You’ve been highlighting the link between ancient history and contemporary techniques. Does this have anything to do with media archaeology? You mentioned Siegfried Zielinski, with whom you studied at the European Graduate School. How can the archaeological approach be useful when it comes to understanding the use of abstraction in Teoman Madra’s video art? (Because you told me you’re preparing a book on Madra temporarily named Soyutlmalar, the Turkish word for “abstraction”…)

S. A. : Indeed, Zielinski was teaching media archaeology at the European Graduate School. His thesis was on VHS technology in the ’80s, for instance. He spent a lot of time in the archives, digging so deeply, even going back to the 3rd-4th century China, and going through this Islamic enlightenment period in Bagdad and Damascus and all these cities. He was trying to seek the hints of what we are seeing today, which is called “media arts”.

There is a notion I’ve always been criticizing, the idea of “new media”. “New media”, from a philosophical perspective, is a cliché. “New” is a term which we’ve been borrowing a lot from modernity, a period which broke away from tradition and is very much based on consumerism. I think we should go back to that history from Zielinski’s perspective, do this excavation and find this cultural inheritance before us.

The reason why we, Turkish artists, are more exposed to abstraction has a little to do with religion practices over here, of course. Abstraction was quite a strong ingredient of Islamic art. Islam wanted to distance itself from symbolism, considering symbolism was linked to a dogmatic approach, where the whole story is told from the top, you know. I don’t mean to criticize, but to talk about two different approaches. I’m not the best person to talk about Christianism but, from an observer’s point of view, when I’m inside a church, there’s a lot of symbolism, I’m told a story, and it’s very difficult to question that story. That’s what I mean when I say it’s a dogmatic approach.

Going back to the Islamic point of view, you can see Islam chose abstraction instead, because the idea of a Creator is, by definition, abstract. We have no clues about what it looks like. It’s all about thinking and trying to find him, spiritually. So when you’re inside a mosque, the fact of being away from the symbolism gives you a feeling very similar to the one you get when you’re entering an immersive space. I’m creating those geometric patterns, and I did once an exhibition in an immersive space. That’s when I drew a parallel between those two experiences.

It depends, of course, on the architecture: in this case, I’m talking about the ones built during the period of Selçuk’s dynasty. Islamic abstraction is not only decorative, it also has echoes to the Hellenistic period, which preceded the Ottoman Empire. It’s the idea of platonism, of course: there is a heaven with perfection, while the earthly world is impure, mixed. This applies especially to mathematics: we agree on axioms (for example, we say in three points there is just one plane [if they’re not aligned, NDT], and within two points there passes just one line), and these axioms can only exist in a perfect world, but not in our world, which is not perfect. The same approach applies to the idea of a Creator, which is perfect, and of which we’re mere reflections.

So that’s something that I respected and understood practically. When you are drawing things with digital tools, for instance, you’re so prompt to errors. And by doing these errors, you realize you’re not perfect. It’s the same thinking tradition. So abstraction, in that sense, is something we are much more familiar with, historically.

D.: How do you see the next steps of your research? I imagine that archiving and working on Teoman Madra means recreating a chronology of his work. Is it possible to identify periods in such a prolific body of work? There are a few obvious landmarks, such as his 1989 multi-screen installation at the Atatürk Center, which marked a milestone in the development of Turkish media art…

S. A. : At first, I was gripped by the urgent need to safeguard these archives by digitizing them. So that’s what I did, without waiting for any funding. During this first phase, which coincided with the period of the pandemic and containment, I naturally categorized the archives, creating a kind of taxonomy. But the priority was to digitize everything, not to look at what was inside. Master’s student Bergum Celik helped me find the right structure for my database. We found the CDWA standard, proposed by the Getty Foundation, and applied it to our material. We also published a few articles and gave lectures, so that others could join us in this work.

My research project, which was originally an independent project, transformed thanks to the people from Salt (a Stamboulian cultural center, exhibition venue, bookshop and cinema), who run a research program and wanted to accompany me in my exhibition projects and archiving process. I believe that this companionship will help me to think more precisely about periodization. This work has to take several dimensions into account.

One obvious dimension is technological evolution, which we already addressed. But you can also look at Madra’s work from the point of view of his life. I think it was in 1965 that he lost his father. Then, shortly after, his older brother, who had replaced his father, dies as well. So then all the job is on his shoulders. I think that’s one critical moment in his life. Another critical moment in his life is in 1983: he finds out he has colon cancer. But he survives, despite a relapse in 1989. Some people before me thought his abstract spirals had to do with his health condition. Anyway he survives, but the family business doesn’t go well and he tries to do something commercial. He establishes a photo studio and tries to shoot some fashion photos. But he doesn’t have this…let’s say this feature of being commercial. His artworks don’t sell, so that’s the challenge. But no matter these things are happening, he’s still consistently producing things.

The main difficulty in classifying this work is Madra doesn’t have a systematic approach, he’s exhibiting things on periodic occasions. Traces of his exhibitions are very difficult to find. Technological approach is very obvious because it’s global: it’s easier to know. That’s the reason why, in this book that I’m working on, I’m talking to the people who knew him, and the book will be made of these conversations and interviews with people talking about Teoman Madra. So everything could be a little bit chaotic, which is possible. As I also said yesterday, the number of positives and negatives is close to 19,000, a colossal database.