FIDMarseille, 2022

Over Hill and Dale

Occitane Lacurie et Barnabé Sauvage,

Stefano Miraglia,

le 27 juillet 2022

Do we need to remind ourselves that sometimes, in cinema, certain images are not on the same side as others? And that sometimes the film festival, despite its friendly and festive nature, is not necessarily synonymous with unanimity, but plays the delicate role of highlighting contrasts? For us, whose columns have been devoted several times to defending films (by Pedro Costa, Nicolas Klotz and Elisabeth Perceval, Sylvain George and others) and approaches (such as that of PEROU) of hospitality towards migrants, it was important for once to return, and at some length, to a film with the opposite concern. Without claiming to see in it definitive proof of the right-wing drift of French cinema, or a fatal symptom of its accelerated fascistization, it is part of our recently recalled “critical function” to reiterate our position. But also, to show how, conversely, the most beautiful films presented at FIDMarseille can allow us, once again, to broaden the horizon.

Nauseating algae, to say the least

The Breton coast, a charming AirBnb by the sea, populated by young Parisians on holiday. These are the “young people” of today, of this “offended generation” that abandons meat in favour of its soya substitutes, and decries sexism and racism at every turn, including when a horde of zombies smashes down the door of their house. “Welcome zombies! Come on, let’s welcome the zombies!” shouts one of them, the most vocal, waving a white flag. But when the creatures of the night chase her down the stairs, they end up, unsurprisingly, devouring her backside. “No, stop! Okay, I can understand that it’s part of your culture, but here…” cries the candid defender of the oppressed as she dies under the bites of black-skinned zombies with glued-on braids. Is this the new summer fiction from Valeurs Actuelles[11][11] A summer fiction for which the far-right newspaper was condemned for racial insult against the deputy Danielle Obono. The author imagined the representative of the nation propelled into the past, brought to slavery, undergoing all sorts of torment, but always excusing at all costs those inflicted by the African characters, in the name of an uptight intersectionalism.?

No, this is the latest short film by Antonin Peretjatko, a filmmaker invited previously by the FID in 2021 for Rendez-vous du samedi, devoted to the “gilets jaunes”, but who one wouldn’t guess to be the source of a particularly virtuoso revival of the racist zombie film under the guise of adolescent humour. For those who get past the stupefaction caused by Algues maléfiques (Evil Seaweed), its scenario as well as its figurative choices are not without interest in studying a new stage in the progressive breakthrough of far-right tropes into political discourse (and here, artistic discourse), which sneak in at the whim of a confusionism whose name a recent essay suggests: ecofascism.

This group of characters has only one function in this falsely ecological fable intended as a joke: to poke fun at the naïvety and even stupidity of millennials softened by intersectionality and single-sex meetings. The ridicule of cultural relativism, a process well-known in right-wing argument, is thus reinforced in a scene that recalls the worst moments of the controversy surrounding the reception of Syrian refugees in Germany in 2015. While the right quickly suspected these refugees to be the source of sexual assaults and rapes during New Year’s Eve in Düsseldorf, humanitarian aid was then accused of blissful complacency towards the migrants, who were then painted as “enemies from within” and threats to the Western supposedly protective model towards violence against women. And the context doesn’t help: the attack on the house goes back to the less avowed origins of the zombie film (the invasion of the cabin by the revolting slaves at the end of Birth of a Nation, to name but one) in that it discards the Le Bihan-zombie and the scientist-zombie of the beginning of the film and, seems to keep only racialised zombie extras.

Les Algues is thus situated at an original point of intersection: if the film mobilises the most legitimate ecological struggles, those denouncing the industrial-ecological scandal that the State has been judged guilty of allowing to proliferate in spite of the damning reports of associations (by which it might seem to be in keeping with the usual programming choices of the FIDMarseille), it does so by perversely associating it with another supposed “crisis”, that of so-called “migrants”. This argumentative short-circuit, achieved thanks to the similarity in the location of these two “disasters”, the beach, thus makes it possible to identify the two “threats”. The association of these wandering bodies with toxic and proliferating algae then recalls, and perhaps not entirely incidentally, the eco-racist metaphor considering the weed as the antonym of the “rootedness”, proper to the national community, finding in the disconnected “bobos” [bourgeois bohèmes] its useful idiots and even its objective allies. “The specificity of the ecofascist appeal to nature”, as described by Antoine Dubiau in Écofascismes, can be seen as an imperative that identifies the need to “preserve nature in order to preserve the race”, by “protecting it from deterioration from the outside”. Peretjatko’s film thus largely abounds in this conception, according to which “non-native (outside the community, i.e. non-white) populations are seen as disruptors of the nature-race/land-identity ecosystem, in a veritable ecologisation of the fantasy of the great replacement[22][22] Antoine Dubiau, Écofascismes, Caen, Grevis, 2022, pp. 163-165..” At the bottom of such an ideological painting (for what game with characters does not, in the end, claim to play with representations), Peretjatko’s film lends credence to the idea that cultural differences must be “treated” with the same medicine as the nauseating silt washing up on our very own beaches[33][33] A parallel already fomented in 2016 by Jared Kushner, Donald Trump’s son-in-law and media adviser during his presidential campaign, who had expressly requested that propaganda spots dedicated to Mexican migrants filmed by drone in the process of crossing a hypothetical border be broadcast during the commercial breaks of the well-known zombie series The Walking Dead..

The argument of absurd humour, political incorrectness or the famous second degree in which all well-managed dog whistling knows how to drape itself. However, the images have a meaning, the gags too, and the film can be summed up very simply: in a teenage farce, a forty-eight-year-old director uses the imagery of welcoming refugees and turns it as a weapon against a generation that is more involved in the fight against discrimination. What a courageous and refreshing irreverence for the France bollorisée [44][44] After Vincent Bolloré, the process by which media becomes an instrument of propaganda for the alt-right. of 2022.

Valleys of the Commons

What a distance between this discourse and the journey proposed by Marie Voigner in Moi aussi j’aime la politique . The documentary is a production of the Nouveaux Commanditaires, a unique mechanism that aims to bring together actors in democratic life (associations, clubs, groups of residents or local authorities) and artists to whom these groups of citizens wish to place a commission. According to the Nouveaux Commanditaires website, this “protocol” aims to closely link the work of art and the needs of a community wishing to take control of its image(s). In Marie Voigner’s way of filming a territory, the Vallée de la Roya, and the people who inhabit it, volunteers, long-time Royasques committed to welcoming people, Royasques who arrived more recently by crossing the border, the particular production conditions that presided over the birth of the film are immediately apparent. Moi aussi j’aime la politique does not claim to be exhaustive, nor to totalise the experience of hospitality through this specific case of the French-Italian valley. Rather, it is a humble, precise and careful approach, entirely focused on the filmic weaving of a de facto community composed of people who, in one way or another, have come to the aid of refugees on both sides of the border. Since the legal and media troubles of Cédric Herrou (who does not appear in the film, Marie Voignier having chosen a collective approach to hospitality in Roya), this region has been known to be a particular point of intensity in terms of passage and even the topological symbol of the French struggle against borders and in favour of reception. However, rather than the militant iconism that haloed the valley, Moi aussi j’aime la politique choses to focus more on the individual, even intimate, and sometimes painful journeys of people who are sometimes exhausted by the place that commitment takes in their lives, by the growing difficulty that the most elementary gesture of solidarity poses because of the ever more intense repression, by the repeated humiliations of the police and the justice system aimed at discouraging the Royasques. This point of view adopted by Marie Voignier, attentive to the consequences of the struggle over time, makes it possible to appreciate another repressive strategy employed by Fortress Europe: the technique of siege, in other words, the moral siege delivered to a community that the states hope to “wear down”.

A film with a friendly title, Le Passage du col by Marie Bottois, will be of particular intensity for anyone who has undergone the insertion of an IUD – the filmmaker herself recalls the discomfort and contractions she experienced during her first insertion by a hurried gynaecologist. However, the filmmaker does not intend to undergo this insertion, as an additional and invisible procedure to which the female body is so accustomed, not to say resigned. As an “operator”, almost in the same way as the midwife (whose performance not only as an actress but above all as a health professional deserves the highest distinction of the genre), the patient merges with the filmmaker, thus becoming active once again through the means of cinema, even though she is immobilised in the posture imposed by the stirrups. “Rolling”, “cut”, the camera obeys this pallid woman, who moments before had paled in front of the sinister Pozzi forceps. However, there is no question of Marie Bottois staging any kind of revenge on a past ordeal from which she would emerge more “powerful” after having overcome it: the sound sequence is there to give voice to the conversations that initiated the shooting, the laughter in the cuts, the complicit feverishness of this small community, which is given substance by shooting on film (16mm and 8mm) and then the development by the women’s collective L’Etna (of L’Abominable). It is as if this format, which is conducive to workshop work (from filming to development) and to a material relationship with the film, prolonged all the careful and attentive gestures of the IUD fitting, during which the midwife offers the director the chance to touch the copper object, or the wires she has just cut. The film was then echoed by Wendelien von Oldenborgh’s Obsada , a film also devoted to workshop logics, showing that victorious feminist perspectives are conjugated in the feminine plural: that of re-enactment, of reflexive discussion, and of the claim of representation.

What might an anarchist film look like? Cyril Schaüblin’s Unrueh proposes several avenues. Its formal choices (the frame which dismantle the usual hierarchic structure of the image, by emphasising the details of the background or by willingly dissociating the point of view and the point of listening) are in line with the narrative writing proposed at the opening of the film: “I am not the protagonist”, says Piotr Kropotkin, the hero of anarchist literature in the midst of his intellectual formation, here embedded in the living, struggling mass of the trade unionist milieu of another valley, that of Saint-Imier. The mythical place of the Anarchist International (Mikhail Bakunin led an important network there from 1871-1872, influencing the powerful Jura Federation) is thus not only the breeding ground of the theoretical vitality of revolutionary syndicalism, but also the territory of a sensitive geography, of which the cartographer Kropotkin wrote the popular land register in 1878. For whoever names the space has control over it, he states on several occasions, seeking to restore to the inhabitants of the place control over their own space (in the manner of the filmmaker, who discreetly marks himself out as the historian of the minores (the lesser-thans), of the syndicalists, and in particular of the women so important in the anarchist movement).

The inhabitants of this space are constantly threatened by the chronometric standard instituted by the powerful director of the local clock factory, who prides himself in possessing clocks that are more precise and better wound than those of the town hall. Even more restrictive than this private appropriation of a supposedly “universal” measure (the film invites us to counteract this feeling of evidence by reminding us of the constructed nature of all social facts), the factory’s foremen constantly bully the workers in this precision trade, using the latest methods. Measuring the time of each operation with one hand in order to have a rational assessment of productivity, the all-powerful Swiss capitalism with the other hand negates any insurrectionary tendencies, and gently defuses the actions of the anarchist network by removing from its members any means of subsistence. This is the paradox of the Swiss political situation, which is as tolerant of the circulation of democratic ideas – even the most radical ones – as it is quick to regulate this freedom of the press and of conscience by means of a fierce nationalism, maintained by the ruling class through the exaltation of the battles fought for Swiss independence.

Unrueh, or in English the “unrest”, a mechanism at the heart of the clockwork, thus stages the representation of a subtle political balance between antagonistic historical forces. By avoiding the easy solution of a cliché (and in many ways essentialist) representation of anarchy as a brutal break with all social norms, Schäublin places at the heart of his narrative the notion of organisation, so important to the trade union solidarity that reigns inside the factory (where the workers pass the word to each other in order to reduce the work rate) as well as internationally (the reading of numerous letters from foreign federations – Italian in particular – punctuates the life of the workshop). If not perhaps until the last shot, where Kropotkin’s discreet embrace with the worker Joséphine coincides with the (no doubt momentary) stoppage of the cartographer’s pocket watch, hanging from a branch. This is a discreet Benjaminian reminder of the hope held by the revolutionary classes to “undermine by their action the homogeneous time of history”, that of productive time and the rise of the bourgeoisie, just as others in 1830 “pulled on the dials to stop the day”.

Cadastres. The law of the land

This year, Marwa Arsanios was back at FID with Who’s Afraid of Ideology? Part 4. Reverse-shot (the first two parts were in competition in 2020). After having documented the women’s communes of Kurdistan and Northern Syria (parts 1 and 2) and then the Colombian resistance to the wars waged against the people by the agribusiness multinationals (part 3), the filmmaker now films a struggle of which she is also the instigator, imagined for a hilly region, once again, in Northern Lebanon, where her family comes from. Drawing on both a principle of Ottoman law and a Marxist corpus, Marwa Arsanios films a collective work of abstraction of land from private ownership. The commentary also takes the form of a polyphonic speech: the conversation of three characters elaborating the new contract that will bind the inhabitants to this space. While surveying the landscape, they confront their theoretical corpus: one metaphorically postulates a memory of the land and nature, ontologically opposed to the very principles of belonging and exploitation, the other opposes a more classical materialist conception of land ownership and primary accumulation to this vision of “Gaia”, and the third, recalling a point of Islamic law inherited from the Ottoman Empire, the mashaa, disposing of the indivisibility of the land and its products, since they are the exclusive property of God.

The study of the legal solutions to this communalisation is the real subject of the film, thus placing it in the continuity of experiments that could be described as “artistic-legal”. These aim either to act by using the interstices of the law (this is the case, for example, of the “Cinémathèque de l’hospitalité” of the PEROU laboratory, which aims to have the gestures of welcome included in the UNESCO heritage, of Franck Leibovici’s work with the International Criminal Court or of the forensic videographic practices presented in courts of justice as well as in art centres) or to make points of law visible in order to underline their injustice. This was the case with Roee Rosen’s filmed lecture-like performance Explaining the Law to Kwamé (last year’s prix CNAP and competition Flash) and this year’s feature-length fiction film Kafka for Kids, an over-the-top parody of a children’s programme (including songs and acidic colours). Both absurd works, each in its own way, focus on an exceptional regime of Israeli law providing for several intermediate ages between minority and majority for Palestinian children (“young” from the age of twelve, “tender adult” from fourteen), allowing them to be incarcerated in adult prisons before the age of eighteen.

It is another exceptional regime that Franssou Prenant depicts in De la conquête , through fascinating research among the colonial archives documenting the French presence in Algeria around 1830. Through the reading of the officers’ reports, which each in turn give an account of the spoils and the justification for the massacres, one discovers a history written by the armed-hand, revealing the brutal confrontation of the universalist ideals of the Enlightenment – sometimes candidly worn by the very people who flout them – with the economic and racial logics that preside over the muscular reprisals and iniquitous punishments of Arab tribes. Some of these officers, among the most lucid, analysed the interest in internal security that the setting up of a colonial army had: the troops trained in Africa, used to mass graves, would be all the more docile and efficient when it came to operating (as was the case in 1830 or 1848) against the Parisian revolutionaries. This is the whole point of the filmmaker’s montage, associating the violence carried out on colonised territories with the post-colonial violence exercised against immigrant populations in France a century later: in the geography of Paris, a contemporary shot of which is edited in after the images of the present-day Kasbah, the Saint-Michel bridge from which the Algerian demonstrators were thrown into the Seine is next to the revolutionary prison of the Conciergerie. The second part of the film actualises the colonial presence in the current forms of Algerian urbanism. The construction of wide arteries, particularly ill-suited to regulating the high temperatures but necessary for the modernising (and anti-insurrectionary) design of the French état-major, has durably disrupted the old city and the particular sociabilities that were exercised there[55][55] In many ways, this transformation, which began in a colonial context in the 1830s, several years before the Haussmann’s renovation of Paris that began in 1853, is a founding experiment in urban policing. On the high modernist historical process of transforming urban space into legible space for authoritarian purposes (and on the insurrectionary strategies employed in this context), see James C. Scott, Seeing Like a State. How Certains Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed, Yale University Press, 1998, especially chapter two.. Prenant’s investigation thus provides an image of this transformation process left without memory and, through the combined means of film and archival editing, sheds light on this double material layer of the colonial phenomenon to reveal the “deep time” of colonisation.

Excavations

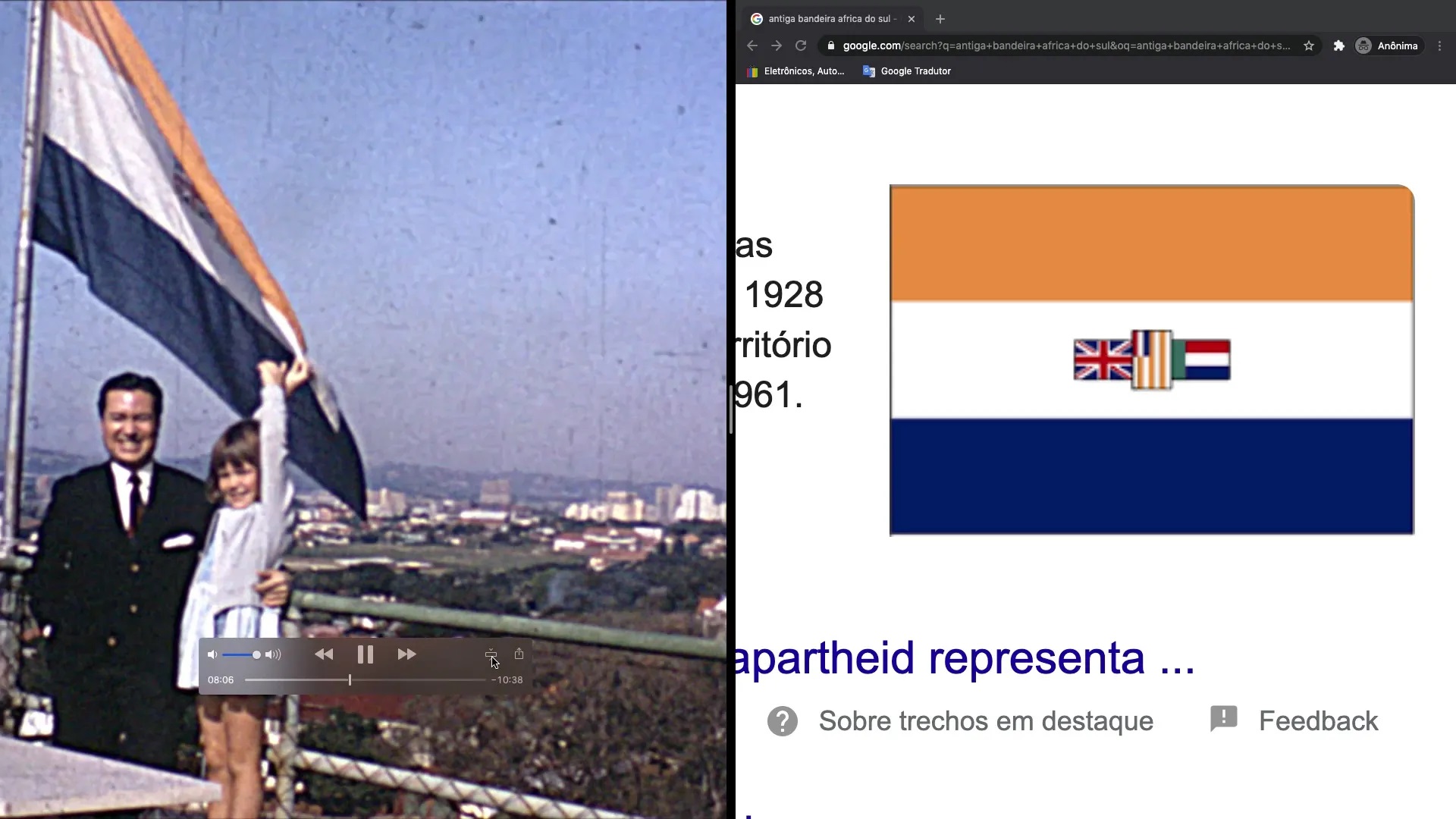

Filme Particular follows the same archaeological movement, except that the archive is the result of a chance finding by the filmmaker, Janaina Nagata, who acquired this “family film” along with a second-hand 16mm projector. Filme Particular then takes the form of an investigation attempting to elucidate the twenty minutes or so of the reel found on the internet. However, it is not a “net found footage” in the sense that the Entrevues de Belfort gave to this term, but rather an old archive whose thread the filmmaker patiently retraces from her desktop. The images come from the 1960s in South Africa, during Apartheid. Using techniques reminiscent of open-source investigation and GeoGuessr, the filmmaker uses the names gleaned from signs, the architecture of buildings and the shape of the shoreline to locate the places filmed by this family and to discover the comments of visitors in the 2020s, some of whom regret the colonial period. Then it is the turn of the faces to become clues: a portrait hanging on the wall, whose figure will later be seen at a garden party and who turns out to be none other than Hendrik Verwoerd, then primeminister and major architect of Apartheid. Then a man posing smiling for the camera, whom a facial recognition application identifies as a renowned witch doctor and a formidable businessman close to the regime. In Janaina Nagata’s film, it is the faces of the powerful that are the object of curious observation, rather than the villagers and their customs captured (and exoticized) by the presumably Afrikaner filmer. Filme Particular unfolds through images of found footage, without commentary (the only voice is the synthetic voice of Google Chrome, which the filmmaker uses to read fragments of texts found during her research) and in grabbling around, which is the great strength of the film. There is no argumentative structure with which the video essay in its desktop form could have familiarised us: Janaina Nagata’s film seems to unfold in real time, throwing up leads that do not lead anywhere, sometimes failing to recognise faces, or seeming to incidentally discover characters or contemporary archives that strangely echo the content of the family film. For example, in a YouTube video, a tourist taking a foreign friend to a traditional festival recalls her childhood memories, “when I was a little girl”, while on the other side of the split screen, the little girl in the found footage smiles at the camera, surrounded by two men in formal clothes.

Also investigating the meanders of visual memory, Ellie Ga returns to the device of Gyres (Compétition Internationale 2020) in Quarries: a light table and photographs developed on transparent material, that her hands arrange to the rhythm of her voice. While the former used an aquatic metaphor both in its structure and in the Mediterranean shores it explored, Quarries has more of a geological, excavating movement aimed at extracting and analysing its author’s memories and the associations of her ideas. While Gyres seemed to rely on the currents of the sea to decide the film’s editing and to make the stranded objects interact with each other, Quarries allows us to penetrate more directly the filmmaker’s stream of consciousness and the effect that the images crossed here and there may have had on her.

Another FID 2020 returnee, Sofia Bohdanowicz, continues her transmedia exploration of grief begun in Point and Line to Plain, where the intermediaries between the filmmaker and the afterlife were her iPhone and her Bolex, whose malfunctions she interpreted as signs from her absent friend. In A Woman Escapes , a three-party correspondence is established between Burak Çevik, Blake Williams and Audrey Benac (the filmmaker’s alter ego, played by Deragh Campbell, who previously appeared under this name in Never Eat Alone, then in MS Slavic 7 and Point and Line to Plane), who mourns the loss of an old Parisian woman named Juliane. The epistolary correspondence is also a filmic and technical correspondence: the artists send each other rushes and sounds, sound commentaries that are constantly rearranged to suit other moods, other images, sometimes filmed in video, in 4K, in 16mm and even in 3D. More than truthful letters from the cinema, the fragments thus shared resemble extracts from diaries (an impression reinforced by the handwritten intertitles indicating dates) of which A Woman Escapes is a collage. Moreover, the moment when Audrey’s grief seems to subside seems to correspond to a form of radicalisation in the choices of cutting and collage that she makes in the materials handed over by her friends. The editing bench appears on the screen, the editor changes locations and voices, appropriates Burak Çevik’s narrative, Blake Williams’ visual experiments and smiles mischievously. The least real character in the film, Audrey Benac, at best an avatar of Sofia Bohdanowicz, gains in consistency as she acts atop reality and her correspondents seem relegated to mere projections of her psyche. The 3D, more than an augmentation of the visual experience, is at the same time used as a means of derealising the spaces it traverses, blurring foreground and background, distorting perspectives, and encouraging the emergence of undecisive forms. With Point and Line to Plane, the filmmaker explained that she wanted to alter the perception of space by transposing images filmed with an iPhone onto 16mm film, or by playing with the detachment of the pressure plate of her Bolex in order to create a doubled vision: 3D then appears as the latest formula for this long-sighted mode of access to the world of the dead.

Tunnel of Love

À vendredi, Robinson by Mitra Farahani (GNCR Competition, already presented at the Berlinale and Visions du Réel) documents a long exchange of emails between Jean-Luc Godard (from Rolle) and Ebrahim Golestan (from Sussex). This correspondence, initiated by Farahani, quickly becomes a wacky dialogue of the deaf, which allows Farahani to paint a close portrait of the Iranian director while at the same time directing the Swiss filmmaker from a distance. Although the film is presented as a correspondence between the two men, it is a real triangulation, as Farahani does not just initiate this epistolary exchange between them, but also lends a hand, adding commentary in voice-over, underlining balances and discrepancies through the edit. It is a film “written at Golestan” and assembled Godard-style. Many of Farahani’s visual quotations and expressive choices make this project a kind of satellite of Godard’s cinema of recent years. A satellite, not a simple homage, because it is clear that this film wants to operate, with a lot of love, something in Godard’s cinema: an additional biographical note, an additional correspondence, an essay on the Godardian shot-reverse shot within a larger discourse, whose core is perhaps Le Livre d’image.

An ascetic film, full of humour and beauty, Pierre Voland’s Signal GPS Perdu (Mention spéciale du Prix national Georges de Beauregard) is a spiritual quest that intersects with a quest for love in a dark forest populated sometimes by wandering knights, sometimes by the notifications of a gay dating app. It took the filmmaker seven years to make his longest and most mature film. Seven years, not only to shoot the fascinating images proposed (of hikes through subjective camera, in winter, in the forests of the Jura) in Super 8, but also to put them to the test, to hybridize them with various types of material: sound recordings of the hikes (so sensitive that they convey the idea of Voland’s body, although we never see it), a fake dating app and its messages, a voiceover reading two texts from Chrétien de Troyes’ Chevalier de la charrette in old French, a song by The Beatles… Voland synthesises different elements: a love of the Super 8 format, cinema as a diaristic practice, the exploration of his own sexuality on the one hand and his Christian spirituality on the other, all through a work of contrast, between ancient literature and contemporary digital communication, between filmic images and writing on a dating chat. Although it may at first seem harsh and severe, Signal GPS Perdu is, on the contrary, a joyful and vital film, a film about existence in the world, a fragment of loving discourse. After a few dissatisfactions and a few blocked users, the protagonist finds an interlocutor and the chat turns into a poetic correspondence. Another love letter appears in this film, more veiled than in Farahani’s film, but clearly recognisable. Signal GPS Perdu is perhaps a kind of love letter to a film that has left a deep impression on its author: La Vallée close, a 1995 film by Jean-Claude Rousseau (also present at this year’s FID with the very beautiful Welcome).

Translated by Elizabeth Dexter.